You might be pals with another girl; you might walk about

with her, and lend her your books and pencils and rubbers; you might even

sit next to her in form - if you could. But anything further was forbidden.

The girls caught walking about with their arms round each other were held

up to keen ridicule; while as for those caught kissing, well, they were

made to feel themselves pariahs.

(Elinor M. Brent-Dyer, A Head Girl's Difficulties, Chambers, 1923,

p154)

Prior to 1949![]() ,

children's books were ignored by the literary critics, and the vast majority

of newspaper and magazine book reviewers confined themselves to brief descriptions

of the novels concerned. An exception was The Times Literary Supplement

(TLS), which contained an annual review of children's books

directed at Christmas gift buyers, either within the main pages or as part

of a separate "Christmas Gift Book Supplement" (which presumably

appeared or not depending on advertising revenue). The Bookman,

an annual publicity journal from Hodder & Stoughton launched in 1891,

also included a review of girls' school stories from December 1896, both

by Hodder & Stoughton and by other publishers, but this was aimed at

a more specialist market led by booksellers. It is the TLS, then,

which provides the most useful record of critical attitudes to the genre

in the first half of the century

,

children's books were ignored by the literary critics, and the vast majority

of newspaper and magazine book reviewers confined themselves to brief descriptions

of the novels concerned. An exception was The Times Literary Supplement

(TLS), which contained an annual review of children's books

directed at Christmas gift buyers, either within the main pages or as part

of a separate "Christmas Gift Book Supplement" (which presumably

appeared or not depending on advertising revenue). The Bookman,

an annual publicity journal from Hodder & Stoughton launched in 1891,

also included a review of girls' school stories from December 1896, both

by Hodder & Stoughton and by other publishers, but this was aimed at

a more specialist market led by booksellers. It is the TLS, then,

which provides the most useful record of critical attitudes to the genre

in the first half of the century![]() ,

since it is the TLS which is most likely to have influenced public

opinion towards girls' school stories up until the end of the Second World

War.

,

since it is the TLS which is most likely to have influenced public

opinion towards girls' school stories up until the end of the Second World

War.

1901

In 1905, the year before Angela Brazil's The Fortunes

of Philippa was published, there were no school stories included in

15 December's "Christmas Books - Stories for Girls" (p448) despite

the fact that the genre was already established. The books selected for

review were: L.T. Meade's A Bevy of Girls, Wilful Cousin Kate

and Dumps, A Plain Girl (L.T. Meade wrote many of the early girls'

school stories, although these were not among them); "Mr Henty"

's A Soldier's Daughter; Annie Fellows Johnston's The Little

Colonel in Arizona; Bessie Marchant's The Queen of Shindy Flat and

A Daughter of the Ranges; Mabel Earle's Molly and Her Brothers;

Mrs George Corbett's Little Miss Robinson Crusoe; M. Bramston's

Rosamund's Girls; Evelyn Sharp's Micky; and Raymond Jacberns'

Crab Cottage. Judging by the reviews, the two most prominent themes

in the books were submission to the needs of the family at home and adventure

abroad, reflecting the books' publication during the heyday of the Empire.

The reviews are largely limited to enthusiastic descriptions of the plots,

since all of the books are recommended to readers.

1902

By 1910, four years after the publication of Angela Brazil's

The Fortunes of Philippa, there are still no school stories included

in the "Tales for Girls" section of the "Special Christmas

Gift Book Supplement" (5 December, p19). The section is divided into

"In Foreign Lands", which consists mostly of reviews of adventure

stories, and "Home Stories", which refers to books with a domestic

theme as well as a British setting. Included among these latter is Angela

Brazil's Bosum Friends, which is described as "none the less

wholesome because the moral is not so obvious . . . a seaside story with

plenty of go in it". "Wholesome" stories were regarded as

being particular suitable for girls, and a "wholesome" theme

was to be a hallmark of a "good" book.

1903

At this point, though, the girls' book market was still being developed, and there were relatively few books being published which were aimed specifically at girls. This is commented on in the boys' book review section, which is titled "The Eternal Boy". (The title may refer to J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan (1904), which was republished in book form the following year, as well as reflecting a readership which included adults.) The section begins:

There is no doubt that there are more girls than boys in England, and most people would say that on the whole girls are fonder of reading than boys. If that opinion is correct, then it must be taken as one more instance of the unequal way in which things are adjusted between the sexes that, in comparison with their sisters, boys get rather more than their share of the good Christmas books that are going. It is possible, of course, that the girls read their brothers' books as well as their own. That would partly account for the apparent defiance of the laws of supply and demand. But in any case the fact remains that publishers and male authors year by year conspire to cater chiefly for the young of their own sex, so that the flood of boys' books is markedly larger than the stream that appeals solely to girls. (p15)

1904

This "flood" includes school stories, and the TLS devotes a separate section to "The Boy at School". This begins with the comment that:

On the whole it cannot be said that any of the school stories published this autumn are appreciably like the real thing, if by the real thing is understood the ordinary public school. The aim of the authors seems to be to manufacture exciting incidents, rather than to grapple with the much more difficult task of allowing the excitement to develop itself, as it does in real life, out of the daily round and common routine of games and work. Also nearly all of them have forgotten that schoolboys are in their own way rather amusing little animals. However, with these limitations, several quite good books are to be found amongst the mass on the bookstalls. (p17)

The reviewer (all of the TLS reviewers were anonymous)

goes on to recommend Ralph Simmond's The School Mystery, E.G. Protheroe's

Nobby's Luck, Percy J. Barrow's Cornered, Harold Avery's

Off the Wicket, John Finnemore's Teddy Lester's Chums, J.

Harwood's True All Through and Father R.P. Garrold's A Fourth

Form Boy - which "in some ways is more interesting than any of

the above . . . partly because it is about a Roman Catholic school, and

partly because it has about it a good deal of the real school atmosphere".

Judging school stories, both for boys and girls, by how closely they imitated

real life was to be the central theme of criticism throughout the century.

1905

During the following five years, publishers began to obey

"the laws of supply and demand", and more and more books for

girls were published, mostly written by women. By 1915, girls' school stories

had become the most popular form of reading for girls, and this is reflected

in the TLS review of that year. It is perhaps significant that the

country had then been at war for more than twelve months, given that the

enclosed world of the school was one of the few where warfare could convincingly

be excluded. In any case, the "Virginibus" section of 9 December

1915 (p462) opens with girls' school stories, which then take up half of

the section. The books reviewed are Elsie Oxenham's At School with the

Roundheads, L.T. Meade's The Daughter of a Soldier and The

Darling of the School, Angela Brazil's The Jolliest Term on Record

and For the Sake of the School and May Baldwin's Phyllis

McPhilemy.

1906

Oxenham's book is praised as making "very good reading aloud for people of all sorts [i.e .boys and girls] who are under fifteen", since it features boys and girls being educated together (albeit for only a term). The belief that "good" books were those which could be enjoyed by both sexes was to grow stronger as the century progressed. L.T. Meade, in contrast, is dismissed as being unlikely ever to appeal to boys, and as producing undesirable reading for girls.

From such breezy surroundings it is a shock to enter the panting atmosphere of Mrs L.T. Meade's stories. Certainly no sane boy would ever cross the threshold of her girls' schools as they are pictured . . . The only males who ever come to these strange abodes are doctors, who pass and repass with surprising frequency, and an occasional parent or elderly sentimental friend. The pupils are divided into sheep and goats, and the mistresses do not scruple to refer to the former as "little angel", "darling child", etc, and to punish the latter with the utmost rigour of the law.

L.T. Meade, never considered to be among the modern genre

writers, was obviously regarded as outdated by this time. It is interesting

to note the mention of doctors, since doctors are the major male characters

in Elinor M. Brent-Dyer's Chalet School series![]() .

Given that the supposedly damaging effects on health had been used as an

argument against girls entering higher education in the 1870s and 1880s

.

Given that the supposedly damaging effects on health had been used as an

argument against girls entering higher education in the 1870s and 1880s![]() ;

the stress which real girls' schools accordingly laid on protecting girls'

health; the fact that in reality doctors would be the males most likely

to enter a girls' school; and the part which accidents and near-death experiences

play in the genre

;

the stress which real girls' schools accordingly laid on protecting girls'

health; the fact that in reality doctors would be the males most likely

to enter a girls' school; and the part which accidents and near-death experiences

play in the genre![]() ;

the constant presence of doctors in L. T. Meade's books is hardly surprising.

More telling is the reference to the "panting atmosphere", with

its associations with both sexuality and gasping for air; the portrayal

of passionate relationships between girls and women which had been acceptable

to Meade's earlier readers and reviewers was now regarded as undesirable.

;

the constant presence of doctors in L. T. Meade's books is hardly surprising.

More telling is the reference to the "panting atmosphere", with

its associations with both sexuality and gasping for air; the portrayal

of passionate relationships between girls and women which had been acceptable

to Meade's earlier readers and reviewers was now regarded as undesirable.

1907

This is highlighted by the way in which Brazil's books are praised for containing:

numbers of nice wholesome schoolgirls who are keen on their games and their nature studies and are not above pranks; they are all as much in earnest about their work and play, and especially their ethics, as girls of that age are in real life, and if they are some of them surprisingly accomplished, they are for the most part not prigs.

"Wholesome" content was regarded as being particularly

suitable for middle-class girls, who were supposed to be as sheltered as

possible from the outside world![]() .

Wholesome girls were "earnest" about their work - this suggests

that their studies were not to be taken seriously in themselves - and expended

their energy in team games and nature study rather than in emotional friendships.

Note that the books are also praised for the way in which they reflect

"reality".

.

Wholesome girls were "earnest" about their work - this suggests

that their studies were not to be taken seriously in themselves - and expended

their energy in team games and nature study rather than in emotional friendships.

Note that the books are also praised for the way in which they reflect

"reality".

1908

Despite the large numbers of girls' books being published by 1915, the genre of "School Stories" was still taken to be synonymous with boys' school stories, and this pattern was to continue for the rest of the century. The title is accordingly assigned to the boys' books section. By now it was recognised, in terms of the boys' books, that:

The school story is as much a Christmas institution as a pantomime. Both have their stock characters and their set scenes; in both the powers of light triumph over the powers of darkness; and both are hieratic forms of art, in which the mode of representation is so fixed that it would be sacrilege to introduce a novelty. The writer of the school story must give us sport scenes and "tuck" scenes; gangs of sprightly urchins . . . and masters who, like Homeric Gods, make sudden dives into the conflict and who, like them, are subject to human frailties. (p460)

Having reviewed R.S. Warren's Smith's Week, E.M.Green's The Damper Boys, Gunby Hadath's The Outlaws of St Martyn's and Sheepy Wilson, John Finnemore's The Outlaw of the Shell, Harold Avery's The Chartered Company and J.Barnett's The Skipper of the XI, the section concludes that:

The good school story describes the violent action which engrosses the attention without recalling - like the war books - the tragic side of violence. It is a happy blend of the real and the conventional; the world it transports us into is so far real [sic] that we can share the absorption of the characters in their struggles; and it is conventional enough for us to read of their failures without pain. It gives us facts that we recognize, although it presents them in an intensified form; the sixer that wins the house match would in our drab experience have been a leg-bye; but the truth is there, though idealized, and it takes a shape to arouse happy memories. In fact, a good school story can be read by others as well as boys, for it is an anodyne.

1909

It is most likely that the "others" referred

to are adult men, since the readers seem to be expected to identify with

the reviewer in the experiences which they "recognise". It is

highly interesting to note here that the hallmark of a "good school

story" for boys is not taken to be "realism" alone. Instead,

according to the reviewer, the story's appeal lies in including enough

recognisable experiences to draw the reader in, but then eschewing "realism"

for "convention" - i.e. genre conventions - in order to represent

age-old themes such as the battle between good and evil in a way which

ensures that readers can enjoy the stories "without pain". This

is a very convincing analysis of the reasons for the contemporary popularity

of the boys' genre amongst boys and men, particularly given that it was

written in wartime.

19010

As the war progressed, the popularity

of girls' school stories continued to increase, along with the number of

girls now being educated in schools (this latter fact was, of course, related

to the effects of the war). By the end of the war the genre was well-established,

and by 1920 the "Girls' Books" section occupies a whole page

of the TLS of 9 December, with almost two out of the three columns

devoted to "School Stories for Girls" (p832). Only ten years

after the reviewer had deplored the relatively small number of books being

produced for girls![]() ,

the genre was now facing criticism because of the sheer volume of books

being produced, and the fact that the content of each appeared to be very

similar.

,

the genre was now facing criticism because of the sheer volume of books

being produced, and the fact that the content of each appeared to be very

similar.

Stories for and about girls are poured out year by year

in a cataract which nothing seems to stem. . . . It must be impossible

under present conditions to make many friends amongst the new stories .

. . " 'S matter of fact," said a thirteen-year-old intent upon

new books, "I don't want Angela Brazil this time - I've read several

of her books, and I can not remember all the girls apart; they seem

like the same only with different names. Getting stale perhaps, what do

you think?"

Well, as a matter of fact, some time ago it did seem like that; but now

the remark seems more applicable to other authors, for there is so much

go and spirit in Miss Brazil's The Princess of the School . . .

that Miss Thirteen will probably reverse her decision when she reads it.

19011

(It is important to remember here that, ten years beforehand,

the number of boys' books being published was referred to as a "flood"![]() ,

so the girls' books are not being treated more harshly than the boys' books

in this respect.) The reviewer goes on to describe the plot of Brazil's

The Princess of the School, which:

,

so the girls' books are not being treated more harshly than the boys' books

in this respect.) The reviewer goes on to describe the plot of Brazil's

The Princess of the School, which:

is most improbable, of course, but her scenery is real

because she writes from experience, and her heroine is a lively figure.

A Popular Schoolgirl, by the same author . . . is more completely a

school story, and tells of the adventures and successes and upsets of the

girls with a breathless vivacity.

There is always a great deal of vivacity too in Elsie Oxenham's stories,

and her plots are as a rule carefully planned, although she is apt to leap

into improbability at times . . .

May Wynne is described as "apt to place her small heroines in the midst of highly coloured adventures in which their nerve and presence of mind rise to heights which are unreal", while the hope is expressed of both Wynne's books and Christine Chaundler's Just Gerry and The Right St John's that:

parents do not read all these books too attentively; if they do, it must make them think with terror of sending any of their girls to school at all. Some of the schools are quite nice, of course; but even in the nicest there is no end to the queer and untoward things which may happen at any moment. And then, too, well-conducted parents might resent their daughters spending so much valuable time as these young women do in being heroines, when they ought to be learning algebra and French - or nature studying at least.

It is interesting to note here that the "real"

elements of the story are praised while "improbability" is criticised;

yet this is precisely the blend which was noted as making a successful

book by the reviewer of boys' school stories in 1915![]() .

Girl characters are evidently unwelcome when they take on the heroic roles

in "highly coloured adventures" necessary to the representation

within fiction of the battle between dark and light, but which are reserved

by society for boys and men. As a result, girls' school stories cannot

be viewed as a "hieratic form of art". It is also clear that,

unlike the boys' stories, the books do not recall memories of the reviewer's

own school days: it seems likely that the reviewer is a man; but in any

case a woman would be far less likely to have been to school herself. And,

as in 1915

.

Girl characters are evidently unwelcome when they take on the heroic roles

in "highly coloured adventures" necessary to the representation

within fiction of the battle between dark and light, but which are reserved

by society for boys and men. As a result, girls' school stories cannot

be viewed as a "hieratic form of art". It is also clear that,

unlike the boys' stories, the books do not recall memories of the reviewer's

own school days: it seems likely that the reviewer is a man; but in any

case a woman would be far less likely to have been to school herself. And,

as in 1915![]() ,

there is a scornful tone in the reference to the girls' lessons, with the

reference to French and nature studies suggesting a view of girls' education

as teaching "accomplishments" and hobbies rather than fitting

them for the workplace.

,

there is a scornful tone in the reference to the girls' lessons, with the

reference to French and nature studies suggesting a view of girls' education

as teaching "accomplishments" and hobbies rather than fitting

them for the workplace.

19012

If "good" books for girls were "realistic", though, certain subjects were regarded as being unfit for girl readers. For example, the reviewer comments of Dorita Fairlie Bruce's The Senior Prefect, the first of the Dimsie series and later to be retitled Dimsie Goes to School, that:

the girls start a strike; it seems a pity that the idea of strikes should be introduced even if they are condemned, as is here the case. Young people can learn all they want about such things from public news; there is no need for them to apply the strike motive to their own affairs. But there is a very jolly junior in Miss Bruce's story - a certain Dimsie, who can never be made to understand the etiquette of prefectdom and of authority in general; her presence brings geniality into a rather stilted atmosphere. She compares, indeed, refreshingly with Doddles, by Agnes Adams . . . for really, in contemplating this young person, one can only sigh and pass on.

May Baldwin's A Riotous Term at St Norbert's is criticised for being:

really mischievous, because the children in it keep such a low standard. It is all very well to describe naughtiness and snobbery; it is another thing to represent complete lack of discipline in such books as these, and even though a sort of fairy-tale transformation takes place, such a habit of writing must be deplored.

"Good" books, then, are expected to provide

a "good" example and influence with clear moral guidelines.

19013

"Bad" books are those which contain "sentimental" elements, although they are criticised primarily for being a dated portrayal of girls' schooling rather than purely being "unrealistic". For example, of Roseleen at School the reviewer notes:

May Wynne ends her books with the question, "Who does not love Princess Roseleen?" It must be confessed that the reviewer is very far from loving her. She seems to belong to the sentimental L.T. Meade period rather than to the merry maidens of to-day.

The continuing denigration of "sentimental"

portrayals of school life is telling. Close emotional relationships between

girls were perceived as encouraging lesbianism and women's independence

from men. As Auchmuty points out: "Feminist scholars assign the beginning

of systematic repression of women's friendships to the 1920s, and there

is much evidence to support this view."![]() It is also interesting to note that "breathless" is used here

as a positive adjective to describe Brazil's books, whereas five years

previously, "panting" had been used as a criticism of L.T. Meade's

It is also interesting to note that "breathless" is used here

as a positive adjective to describe Brazil's books, whereas five years

previously, "panting" had been used as a criticism of L.T. Meade's![]() .

Is this because being breathless denotes an inability to act, whereas panting

suggests active sexuality?

.

Is this because being breathless denotes an inability to act, whereas panting

suggests active sexuality?

19014

On 8 December 1921, the "Books for Girls" section again occupies an entire page. It opens with another criticism of the sheer volume of books being produced in the genre.

When one sees the numbers of new stories of all sorts which are poured out year after year one wonders if any present-day girl has the past-day custom of reading a book twice. If they are to keep up with the flow they certainly never can; and it seems that they do keep up with it or else it would surely slacken. (p620)

The size of the genre and the similarities between individual

books was to become another constant theme of criticism. This is in sharp

contrast to the tone of the 1915 review of boys' school stories, where

it was recognised that the genre has its "stock characters and . .

. set scenes . . . the mode of representation is so fixed that it would

be sacrilege to introduce a novelty".![]() The tone of the 1921 review may also have been due, though, to the fact

that the reviewer was forced to read every example of the genre published

in a particular year, which might well have been sufficient to deter even

the most enthusiastic schoolgirl reader.

The tone of the 1921 review may also have been due, though, to the fact

that the reviewer was forced to read every example of the genre published

in a particular year, which might well have been sufficient to deter even

the most enthusiastic schoolgirl reader.

19015

It is noticeable that "School Stories" take up less than a third of the 1921 section, being considered between "Australian Stories" and "Unattached Girls", which indicates that the girls' book market had now widened. The school stories reviewed include Angela Brazil's A Fortunate Term and Loyal to the School, Dorothea Moore's The New Prefect, Christine Chaundler's The Fourth Form Detectives, Dorita Fairlie Bruce's Dimsie Moves Up, Doris Pocock's Margery Finds Herself and Elsie Oxenham's The Girls of the Abbey School.

It may well be asked where all these ladies first met all these girls and whether they spend their entire time, always excepting the brief hours spent in writing books, travelling from school to school all over the country? The results of their endeavours are usually quite harmless, often quite amusing and seldom very invigorating.

A lack of respect for the women who wrote school stories

was also to become a recurring feature of criticism. Once again, "good"

books are judged by their "realism" and lack of "sentimentality".

In Loyal to the School, "Lesbia's struggles to subdue her ardent

impulses are sympathetically handled and the sketches of other characters

are touched in with experience", while Moore's, Oxenham's and Bruce's

books are also recommended. Dimsie (in Dimsie Moves Up) "is

even more in the centre of the stage; but she is quite an entertaining

little body, and, however unconventional in its activities, her 'Anti-Soppists'

society is one to be cordially approved of". But in terms of "bad"

- "unrealistic", "sentimental" or "soppy"

- books, Pocock "errs on the side of extravagance", while "the

girls at Miss E. Everett Green's Queen's Manor School . . . might well

have had an 'anti-soppist' society of their own", and of Baldwin the

reviewer writes that "perhaps she, too, should join Dimsie's society!"

19016

On 7 December 1922 the reviewer yet again begins by commenting on the number of girls' school stories being published.

The flood of books for girls of all ages is everywhere in spate, and from it are cast up some pleasant things for those who care to risk disappointment by the way of getting them. Of course, year by year a good deal of rubbish is cast up also; one wishes it could be carried away once for all [sic]. There is a certain class of story which although not actually harmful is vapid; stories which contain little else than a chronicle of school gossip, the description of various childish escapades in which the heroines are entangled, and which invariably entail a great deal of limelight for the principal characters, cannot do anything towards the permanent enjoyment or employment of their readers. Indeed, the question of school stories is one which writers for girls should consider seriously. It may be possible to preserve a certain proportion in the events described, though too often the reality is sacrificed to effect, but it is very seldom that such efforts have any spontaneity at all; and spontaneity is the essence of writing for young minds. (p816)

Books where girls receive "a great deal of limelight", then, are "rubbish". It should be noted that: "Miss Dorita Fairlie Bruce keeps her girls singularly fresh" in Dimsie Moves Up Again; Dimsie receives a great deal of attention in the course of the book, but never steps outside of a conventional female role. In contrast:

The way in which they managed things at Pen-y-gant School (The New Girl at Pen-y-gant, by Miss Dorothea Moore) . . . led to a great many odd happenings, including escapes from death by earth, air, fire and water. It is all very highly coloured and harmless, though the adventures of the new girl bring her a great deal more notice and success than she deserves. Miss E.L. Haverfield's Just a Jolly Girl . . . has far-fetched adventures too, so far-fetched that the ordinary reader will thankfully count up her numbers of friends who remain "awfully jolly girls" without any adventures at all. But there is quite a nice headmistress, and the alarums and excursions are for once due more to a crazy gardener than to the usual heroic figures in "gym" clothes. But why will writers still rely upon "wild" Irish girls, who call their brothers "broth of a boy"?

Christine Chaundler, in A Fourth Form Rebel and The Reformation of Dormitory Five, makes "little attempt at characterization", while "Miss Kathryn Rhodes's Schoolgirl Chums . . . belongs to the same category; it details the wearisome adventures of the usual high-spirited daughter of a V.C. father (there are so many V.C.s in these volumes) . . . "

There is more school gossip, a great deal of it, in Binkie of IIIB, by Miss Evelyn Smith . . . Gerry Goes to School, by Miss Elinor Brent-Dyer [her first published school story] . . . and Angela Goes to School . . . by Miss May Wynne, but in none of them, nor in Miss Alys Chatwyn's A Credit to the School . . . does any character emerge in a wholly life-like condition.

Of the latter book, the reviewer concludes that "Those

who like it can go on with it until page 240, but there will always be

those who do not". Characterisation, along with a "realistic",

"wholesome", non-"sentimental" portrayal of girls'

lives, was to become the hallmark of quality for the TLS critics.

For example, Angela Brazil's Monitress Merle is recommended as:

"a rambling, wholesome story with as many turns as the Devonshire

lands in which it is set".

19017

On 29 November 1923, the reviewer notes that the choice of books for girls is continuing to widen, with the introduction of books set in the contemporary girls' movements of the Girl Guides and Camp Fire girls.

Judging by this year's harvest of gift books for girls, the school story still leads in popularity; a lesser demand is apparently made and met for the domestic tale . . . There is a small supply of books about Guides, Brownies and Camp Fire girls which may create an increased demand; it is to be hoped so, for these are at any rate healthy open-air stories which may counteract the effect of the innumerable books which give a sentimental or sensational view of school life. (p830)

Books where girls have passionate friendships or act heroically are clearly shown by this statement to be "bad". For example, Dorita Fairlie Bruce's The Girls of St Bride's and Ethel Talbot's The Sport of the School "depend rather less for their interest upon school politics than upon the discovery of missing heiresses and disowned relatives", while "In Jean of the Fifth by Winifred Darch there is a 'Russian Spy' mystery which is hardly necessary to the interest of a story already full of lively schoolgirl incident".

It seems too much of a coincidence that Beatrice, in The Head Girl at St Bee's . . . by Alys Chatwyn, should be the double as well as the namesake of Princess Beatrice of Urugalia. This does not, however, interfere with a crowded school career, full of school sports, dangers from flood and fire, and the anxious responsibilities of a senior girl. It is only in the holidays that she is kidnapped and induced, for political reasons, to impersonate the princess. The overcrowded incident in this book should have furnished forth two good stories, leaving room for a little characterization by the way. There is some originality in Betty the Ugly Duckling by Doris H. Pocock . . . Miss Pocock has developed an interesting story from the beginning, and it is a pity that she could not resist the usual rescue from fire at the end. Why are all these schools so flammable?

19018

It is interesting to note that the reviewer did find some school stories which met their own criteria.

Miss Evelyn Smith is a discovery. Here is an author who can write sympathetically of schoolgirl friendships without sentimentality; who can make her story interesting without the help of a single "sensation"; and who compels the reader to laugh heartily at conversations and incidents that have no hint of the farcical. The characters are so well drawn that we can even remember The Seven Sisters of St Anne's . . . apart without an effort - especially, perhaps, Tony, who is writing a novel, "The Bittersweet of Life". The Little Betty Wilkinson is another attractive book by the same author.

Other school stories which the reviewer recommends include:

Dorothea Moore's The Only Day Girl; Jessie L. Herbertson's Betsy-Go-Lucky

("sensible girls will enjoy it all the more because it is convincing");

Katherine Oldmeadow's Princess Charming ("It is a relief, by

the way, to find a 'Princess Charming' who can attract her schoolfellows

without making herself too much of a nuisance to her teachers!");

P.T. Hinkson's The Girls of Redlands ("We cannot quite believe

in Irene . . . nor in Sir Terence, the picturesque ghost; but the story

should be quite popular"); Nancy M. Hayes' Peg Runs Away to School

("it is rather a relief to find that . . . it is to a school which

has 'earned a name for strictness and discipline'"); Christine Chaundler's

Jan of the Fourth ("a book for the hockey girl") and Captain

Cara; and Dorita Fairlie Bruce's Dimsie Among the Prefects ("this

is a sequel to other adventures of 'Dimsie's', but all necessary explanations

are introduced naturally into the early pages - a great virtue in sequels").

Christine Chaundler's Tomboy Toby "has a more connected plot

and more unity of interest than the average", while "Conscientious

senior girls who wish to quell an episode of sentimentality in their school

should certainly read A Head Girl's Difficulties by Elinor Brent-Dyer",

and Angela Brazil's Schoolgirl Kitty has "the added charm of

an account of student life in Paris and a sketching party in Brittany -

very well told and lifelike".

19019

On 20 November 1924, the two columns which the TLS devotes to "School Stories for Girls" (p764) include the same themes as before. Too many books are being produced, and their content is too similar and too exaggerated with poor characterisation. Distinctions can be made between "good" books, which are wholesome, realistic and set a good example to readers, and "bad" books, which are sensational and/or sentimental and are a bad influence on readers, but at best the genre is a distraction from "better" reading, which means reading books which could be enjoyed by both genders. Last, but by no means least, "lady" authors should not be taken seriously; .

Girls must often be rather puzzled by having so many "books

for girls" thrust upon them, when for those, and they are many, who

really care to read there are such fields of happiness in books of all

kinds without special labels. It is to be assumed that all the ladies who

turn out year by year this mass of volumes take themselves and their work

seriously. If they did not, it might be so much better. For it must be

said that generally what are called books for girls leave much, very much,

room for improvement. A ceaseless flow of petty gossip about schools, details

of girls and mistresses, of feuds, adorations, of cheating, of games, and

the like, is poured out year by year in well-printed, brightly bound volumes

by a large number of authors. The same ingredients with here and there

a new flavour make the pudding, the same old pudding.

It would be easier to pass over such stories in silence, recording only

those which are pleasant to read and which have some definite characteristic

to save them from the general run. But since year after year so many writers

continue in the self-same way, there must be some reason worth enquiry

for their persistence. Why, for instance, should Miss May Wynne produce

one after another five volumes, all of which, in spite of bright get-up

and a certain sprightliness, bear the marks of machine make

in a most deadening way?

However, the question is left unanswered by the reviewer,

who goes on to criticise May Baldwin's The Brilliant Girls of the School;

Kathlyn Rhodes' Head of the House ("there are some very naughty

girls . . . and it needs much tribulation to set them on the path of virtue

and also the well-known expedient of desperate illness"); Constant

Mackness' Miss Pickle (which "leads her readers into a very

bog of sentimentality"); and Lilian Turner's Jill of the Fourth

Form ("she would have us believe she has turned a spoilt baby

into an heroic girl. But how does she tell of the change? 'Oh! throbbing

tune, fraught with moments big as years,' she cries; and it is not a cry

likely to appeal to the young").

19020

Nancy Hayes' Fourth Form Invaders and Edna Lake's The Right Rowena, however, have "a definite thread of storytelling"; the latter, "though having a quite impossible plot, involving changed babies and a tell-tale mole on one shoulder, yet has some pleasant girls in it and some quite human teachers".

It is unfortunate that so many of these stories dwell upon petty thefts and other unpleasing and on the whole unusual misdemeanours among girls. Both Sally Sticks it Out . . . by Miss Christine Chaundler . . . and Heather at the High School, by Miss Winifred Darch . . . make a good deal of the thieving theme. But both have also another string to their bows - a genuine desire to put forward the claims of scholarship girls from primary schools in secondary schools. Snobbery is a human failing, quite as common, therefore, and quite as cruel among children as among grown-up people. But it is hardly possible that Miss Chaundler's "Sally" could in real life have fallen in with such a mean set of girls or such a singularly blind set of mistresses, or that she would have vindicated herself with such dashing heroism. Miss Darch's Heather and her surroundings are on a less exalted plane and far more natural. Heather and her cottage home are pleasantly described, and her difficulties are treated normally in contrast to more pleasant incidents. The Day Girls' Champion, by Miss Doris Pocock . . . presents another side of the same difficulty.

Josephine Elder's Erica Wins Through also receives the reviewer's approval, but Phyllis Mord's The Taming of Winifred is "a dull story" and "Not much else can be said of Mollie Hazeldene's Schooldays . . . by Miss Maude S. Forsey, which purports to be written by the Mollie of the title, but which bears on every page the stamp of a sophisticated hand".

Miss Ethel Talbot offers a range of schools . . . in The

Best of All Schools . . . Sally at School and The Luck of

the School . . . They deal with such everyday matters in school life

as hidden treasures, long-lost relations who turn up at one's elbow in

moments of need, haunted tombs with doors that clang upon the unsuspecting.

Really "The Mysteries of Udolpho" seem tame in comparison to

the adventures which may befall simple English girls of fourteen in "schools

for the daughters of gentleman", and yet Miss Talbot is by no means

the wildest romancer - there are others who outrun her.

It is a relief to turn from the follies of That Awful Term, by Miss

E.M. Channon . . . Queen's Manor School, by Miss Everett-Green .

. . which apparently was full of quite dreadful people, and Fen's First

Term, by Miss Dorothea Moore . . . to the more breezy atmosphere of

Miss Dora Chapman's first story, That Rebellious Schoolgirl . .

. or to the common sense of Miss Elsie Oxenham [The School Without a

Name].

. . . The last three of the schoolgirl stories to be considered here, and

the most cheering, are Miss Angela Brazil's Captain Peggie . . .

Miss Bessie Marchant's The Most Popular Girl in the School . . .

and Miss M. Bradford Whiting's What Hazel Did.

The reviewer concludes that:

Human portraits are rare in all these stories and worth remembering. Some of the unfortunate writers probably cannot afford the time to dwell with their ideas long enough to give them substance, and some have sadly thin ideas; small fees, the supposed wishes of publishers, keen competition, all these things are a handicap and a temptation. But normal girls do enjoy good reading when it is given to them; and this reiteration of paltry themes must have much the enervating effect on them as royalty ballads masquerading as music have in another art.

19021

It is important to note here that the accompanying reviews

of boys' school stories are more sympathetic. However, by now "good"

books for boys are not only "realistic", but also embody "the

public school ideal". Unlike the 1915 reviewer![]() ,

the 1924 reviewer does not regard "sensational" books as being

characteristic of the genre in representing the battle between light and

dark.

,

the 1924 reviewer does not regard "sensational" books as being

characteristic of the genre in representing the battle between light and

dark.

Most of these stories follow one of two patterns. In one the theme is always, in reality, the public school ideal, which has to be defended against betrayal or neglect: in the other the author fills a school term with a mixture of petty crimes and mysteries, and seasons it with schoolboy humours. The advantage undoubtedly lies with the former; certainly in the batch before us the best stories are of this kind. They have their weaknesses and absurdities, they beg some questions of school life and polity, they are occasionally a little unscrupulous in their massing of all the schoolboy virtues on one side and all the vices on the other, and for these reasons they do not always give an accurate picture of school life. But they have the immense advantage of embodying an inspiring idea. (p766)

Following this comment, there are sympathetic reviews

of Frank Elias' The Two Captains of Texford, Gundy Hadath's Pulling

His Weight, Against the Clock and His Highness, R.A.H.

Goodyear's The Fifth Form at Beck House, Battle Royal School

and Young Rockford, Richard Bird's The Liveliest Term at Templeton,

Alfred Judd's The Mystery of Meldon School, Skelton Kuppord's Hammond's

Hard Lines, Rowland Walker's Shandy at Ringmere School and

The Rival Schools, Ernest Prothero's Boys of the Brigade

and John Mowbray's The Way of the Weasel. None of the male authors

who produced multiple volumes that year are criticised, as May Wynne had

been, for publishing work which bore "the marks of machine make in

a most deadening way"![]() .

.

19022

In contrast, on 26 November 1925, the themes of the reviews of girls' school stories continue as before, with the reviewer now claiming the support of the readers' themselves.

a critic, who is under fourteen . . . remarked sadly that she wished she could find one story about a school that had not any buried treasure in it or near it, and that did not often catch fire; and added that in the schools she knew it was not usual to have as many as three gallant rescues of imperilled lives in one term. Miss Moore, who says she is most influenced by "the critics in gym frocks", might perhaps take this opinion to heart. Even in "Z House" she has not quite got away from fire, flood, and buried treasure. It almost seems as if her heroine, a young house captain striving to restore order in a house that had fallen into bad ways, could not have succeeded in her task without these adventitious aids. This is a pity, for Zella's efforts and feelings are well described . . . The romantic surroundings of the school and the free and pleasant life of its girls are so attractively portrayed that the reader feels a wish to identify with it. (p802)

Other books reviewed include E.L. Haverfield's The Discovery of Kate; Kathlyn Rhodes' School Girl Chums, Margaret Ironside's The Mysterious Something and Ethel Talbot's The Girls of the Rookery School and Neighbours at School - which are all described as reaching "the climax of absurdity in the way of Adventures (with a large A)"; and Edith Elias' Elsie Lockhart, Bessie Marchant's To Save Her School and By Honour Bound, Pamela Hinkson's Patsey at School and Dora Chapman's Betty Plays Up, which are all criticised for their "unreality . . . tinged with very unpleasant sentimentality".

Some of the books give the impression that the writers must be on the same intellectual and emotional level as the very silly girls they describe. It seems a pity that, before writing more, they do not associate for a while, if not with grown-up people, at least with intelligent and sensible school girls, of whom, after all, there are plenty in the world. Above all, they should study the working of ordinary modern girls' schools and should endeavour to become acquainted with some of their staff. Then perhaps they would not dream so much of headmistresses who, though they have penetrating blue eyes, soft golden (or silver) hair, and exquisite clothes, can only get on by threatening their mistresses with dismissal, and their pupils with expulsion, at every turn. The most mawkish of all is Miss Talbot's Patricia Prefect . . . The most ridiculous is perhaps The School Enemy, by A.M. Irvine . . . The Girls of Old Grange School, by May Wynne . . . is more harmless, but distinctly "machine-made"; while Septima at School, by Evelyn Smith . . . is chiefly about picnics. All these books are rather silly and likely to be regarded with some disdain even by school girls with a strong liking for this class of tale . . . Sentimental writers should take note of the disgust which the introduction of a "love interest" in the wrong place may excite in their very young readers. When they do so, such silly books as Rosemary to the Rescue, by Joyce Colmer . . . will cease to be written.

It is interesting to note that "unpleasantly sentimental"

writing is equated with a failure by the writers to develop into "grown-up

people". This suggests a Freudian influence, with lesbians regarded

as being in a stage of arrested development.

19023

In contrast, "two of the most pleasant and readable of the school stories this year are not about boarding schools at all": Evelyn Smith's Val Forrest in the Fifth and Christine Chaundler's An Unofficial Schoolgirl. Day schools did, of course, feature in the genre before this, but were to become more common after the mid-1920s. It is probably that one reason why they were welcomed by the critics is the fact that girls returned home to their families at the end of the school day: parental influence could not be entirely excluded from the books; nor could the schools be portrayed as having a greater influence on their pupils than their domestic environment. Also praised is Josephine Elder's The Scholarship Girl - "even more pleasingly original and natural" - and:

To finish up with, we have two delightful stories of small schools in foreign lands started by Englishwomen who are left with children dependent on them, and who feel, as so many of their like have done from the days of Mary Wollstonecraft onwards, that school-keeping is the only way open to them of at once earning for their dependents and giving them a home. These are The School at the Chalet, by Elinor Brent-Dyer, and The School in the Wilds, by Mary [sic] Baldwin . . . Adventures seem more probable when they happen in Tyrol and in Kenya Colony than in Sussex, and those in these books arise naturally out of the circumstances. The chief characters are also well described; and these last books will, we think, be found interesting by some parents and teachers as well as by girls.

19024

Brent-Dyer was not to fare so well in the TLS again, though. By the late 1920s there had been a distinct change in the direction of the genre, with the authors themselves apparently accepting the justice of the past criticism. Accordingly, on 24 November 1927, the TLS reviewer notes that:

There are some good girls' school books this year. Though

we still find a good many mechanical stories, full of improbable incidents,

some writers for girls do, on the whole, show a greater inclination to

tackle the real problems of school life. There is more attempt at characterization,

and the numbers of secret passages, buried treasures, lost relatives and

miraculous rescues have decreased.

If anyone doubts that it is possible to make a good book without these

ingredients, using only the ordinary incidents of school life, we recommend

him to read Phyllida in Form III., by Evelyn Smith . . . Phyllida

will not, of course, be interesting to those who do not care about girls

(but who that does not care about girls will look into these school books?).

Those who do care will find in it an excellent story and a close rendering

of school life. Nothing happens in it but things that quite ordinarily

do happen to girls between twelve and fourteen . . . the children in it

are real children. (p876)

Similarly, in Josephine Elder's Thomasina Toddy "the different characters are all well described", while Christine Chaundler's Philippa's Family:

is one of the the best books before us this year . . . The problem Miss Chaundler has chosen to write about is that of the rival claims of school and home upon a girl's energy and time . . . This is a book that might make parents think . . . In another book by the same author, Reforming the Fourth . . . the troubles of a good girl in the midst of a crowd of naughty ones are graphically described.

It is interesting to note that Chaundler's first book

has a domestic theme, while the "good" girl in her second reforms

the rest of the school.

19025

Also recommended by the reviewer are Winifred Darch's Cicely Bassett, Patrol Leader, and with reservations Dorothea Moore's Brenda of Beech House ("it might be a waste of a Balkan princess to let her go through nothing but the ordinary experiences of school life") and Winifred Darch's Varvara Comes to England ("a pleasant and, on the whole, natural tale"). However, Christine Chaundler's The Chivalrous Fifth, A.Legion's The Three Helens and Elinor Brent-Dyer's A Thrilling Term at Janeways receive less enthusiastic reviews, while.

For the rest, Miss Angela Brazil [Ruth of St Ronan's], Miss Elsie Oxenham [Jen of the Abbey School] and Miss Ethel Talbot [Jan at the Island School] write the kind of books that their readers have learned to expect . . . Miss Dorita Fairlie Bruce tells some more about Dimsie in Dimsie Goes Back . . . and Miss Brent-Dyer tells us more about the Chalet School in The Princess of the Chalet School . . . Miss May Baldwin writes of schoolgirls in Nice, instead of Kenya, in Rooni . . . and a dozen or more other authors write about all the themes alluded to above and a few others, such as love-affairs and blackmail, both of which are surely most undesirable subjects in school books.

Once again, a "good" book is expected to avoid

"unwholesome" subjects such as love-affairs, and to have a good

influence on its readers. It is interesting to note that the very concept

of genre writing - "the kind of books that their readers have learned

to expect" - is regarded as being "bad". The reviewer concludes

that: "A good deal of rubbish still appears, but on the whole there

is a distinct step forward in stories for girls."

19026

By 20 November 1930, though, the "Girls at School" section has been reduced to less than a column and general comments about the genre have ceased, seeming to indicate that the genre was now regarded with less importance. Perhaps the readers themselves were dissatisfied with the "improvements" which had been made to the genre, since the reviewer continues to find more books which now meet their standard for a "good" book.

Josephine Elder gives us another excellent school story

this year [Barbara at School]. Like the late Miss Evelyn Smith,

whose loss none of those interested in girls' books can cease to lament,

Miss Elder has a keen eye for the subtleties of immature character . .

.

In some ways The Girl Chums of Norland Road School, by Edith Miles

. . . is the most interesting of the other school stories. It is a little

amateurish, and the perfect happiness (including three scholarships) with

which the three heroines are rewarded at the end does not quite carry conviction.

But the description of the school and of the life in it does.

The reviewer continues that "this year's stories by Winifred Darch [The Lower Fourth and Joan] and Christine Chaundler [The Technical Fifth] are, as usual, natural, lively and very readable", with Chaundler's book showing "the peculiar distinctions in the schoolgirl code of honour". However:

There is nothing so original in the remaining school stories. Some, like That New Girl Anna, by Cecily Fox . . . tell of "Ruritanian" princesses taking refuge from their enemies in English schools. Some like Eustacia Goes to the Chalet School, by Elinor Brent Dyer . . . show how intolerable little girls can be converted by misfortune. Some, like Jean's Two Schools, by Ethel Talbot . . . show how girls who are not intolerable to their schoolfellows, but only trying to their mistresses, can be converted by admonition and sorrow till they are fit for anything, even to become Head Girls. Some, like Dorothy's Dilemma, by Elsie Oxenham . . . compare character and show that, though selfishness gets its own way for a time, goodness triumphs in the end. But none of these themes is treated with any subtlety; most of the authors show but a superficial knowledge of the nature of girls. This is as apparent in the well-established writers as in the new ones; going on writing about any particular set of human beings does not, it seems, teach one to know them.

19027

It is interesting to note here that greater prominence is given to reviews of boys' school stories, which occupy nearly two columns of print. However, the reviewer notes the fact that the boys' genre was in reality now declining, and the review indicates that the quality of what was being published was regarded as poor.

It was noted last year that the number of boys' school stories published tended to grow smaller. There are a few more this year, but there is nothing new to be recorded either in the stories or in their authors' methods. There are some half-dozen authors of established popularity who do the accustomed thing pretty well, and some others who do it not quite so well; except for that rough distinction there is little to choose between the various specimens. One moderately good story is so like another that it is sometimes hard to distinguish between them. (p980)

19028

Taken together, these reviews may seem to reflect a decline

in the importance assigned to the school story, but five years later, on

30 November 1935, the "School Girls of To-Day" (p806) section

once again occupies two columns and is subtitled "The Corporate Spirit".

The reviewer accepts that the genre has "improved"; as well as

being "realistic", "good" books are now those which

also reflect the school ethos, and particularly the "public school

spirit" which had been adopted from the boys' schools![]() .

It is interesting to note that the reviewer clearly does believe that "good"

stories can reflect "reality". For example, after a positive

review of E.M. Channon's A Fifth Form Martyr, the reviewer continues

that:

.

It is interesting to note that the reviewer clearly does believe that "good"

stories can reflect "reality". For example, after a positive

review of E.M. Channon's A Fifth Form Martyr, the reviewer continues

that:

After reading through more than a score of newly published girls' school stories it is difficult to resist the conclusion that the great thing girls' education has gained in the last fifty years is what is conveniently summarized as "the public school spirit" . . . The stories now before us show how thoroughly they have assimilated it, and how it has spread from the few schools to the many; so that the attitude of mind which will afterwards be useful to the Country and the League of Nations is already being fostered in the Fourth Form.

In Joan Butler Joyce's In Hot Water:

We return to the large modern public school and see the

reaction to its opportunities of girls with very different temperaments

- the born student, the natural athlete, the humourous would-be cynic,

and so on.

Much as these books vary in merit they all have one advantage over the

girls' school-books most current ten years ago; they are concerned with

the real happenings of school life as it is, and with the problems of character;

not with emergencies of flood and fire. There was a time when one could

hardly open a girls' school book without coming on rescues from burning

dormitories, or from the incoming tide, and it was hard to find anything

else in them, except perhaps a buried treasure, or a secret passage.

The reviewer goes on to stress that, in their opinion:

Angela Brazil was not responsible for these absurdities. She practically invented the girls' school story, and seems always to have understood that its interest must depend chiefly on the development of character. She has not changed with changing fashions, and she describes the kind of school and the kind of people she knows with a good deal of pleasant detail. She does this again in The School at the Turrets . . . As usual she interweaves her account of school events with a quiet family drama, and some descriptions of foreign travel from a girl's point of view.

This is actually a very accurate description of the content

of Brazil's books. However, it should be noted that their popularity did

not survive into the last quarter of the twentieth century, as less "realistic"

books such as Elinor M. Brent-Dyer's Chalet School series have done. "Realism"

was never perceived to be the hallmark of quality by the genre's readers.

19029

The writer goes on to review Veronica Marlow's The

Lower School Leader ("even in the Fourth wrong treatment may drive

'school patriotism' into revolutionary activities") and Dora Chapman's

Beryl the Rebel, which both had themes of self-government; Cicely

Thayer's Feuds and Friendships, "which related the events of

one term at a thoroughly modern school which had all the latest improvements,

including laboratories and domestic science rooms and a window in every

cubicle of the dormitory, but had not yet tried any very novel experiments

in self-government"; and Winifred Darch's The Head Girl at Wynford

and Dorita Fairlie Bruce's Nancy in the Sixth, which "describe

the problems of the elder girls in schools who have to bear the chief responsibilities

for their group".

19030

By now, books set in day schools were prominent in the

genre. As well as introducing domestic themes, this perhaps reflected its

greater "realism", since the majority of British schoolgirls

- particularly working-class and lower-middle-class girls, who formed a

substantial proportion of the genre's readership - did not attend boarding

school. Their experiences, however, were not reflected in the content of

the genre. Day-school heroines came instead from the "impoverished

gentry", victims of changing family fortunes which were often exacerbated

by the Depression and/or the death of a parent, unless they were brought

on by the self-sacrifice of a parent in choosing to enter the medical profession

or the Church. (Unsuprisingly, this theme was to continue following the

Second World War.)

19031

The reviewer, though, seems to accept the veracity of the experiences being described.

A country atmosphere, historical associations, and the problems of poverty are elements in many of the books before us, and make us feel what a very important part day schools in small country towns are playing in the education of girls. Winning Her Spurs, by Madge Smith . . . describes one of these. The fact that she returned home daily enabled the heroine, who was the daughter of a country doctor, to be useful to her father's patients and also to develop her friendship with a delightful pony by whose help she won a triumph in a pageant of local history.

Having also reviewed Mary Gervaise's Mysterious Sally and A.M. Irvine's Quiet Margaret ("lively but somewhat improbable"); Constance Mackness' The Clown of the School ("if this is a correct and typical description, it would appear that modern developments in education and discipline have not gone so far in Australia yet as they have in England"); The Evelyn Smith Omnibus ("she had an extraordinary talent for describing the subtleties of adolescent character"); and Dorita Fairlie Bruce's The Springdale Omnibus ("the girls in it have plenty of life and character"); the reviewer concludes that:

If these books may be treated as in some sort social documents, the study of them would certainly induce the belief that girls' schools are progressing. As for the girls themselves - well, girls have always been full of human nature, and older people have always, since the days of ancient Babylon, grumbled at "the modern girl"; but if it is progress to develop in a new environment a new form of virtue that the old environment did not call forth, then we may say that the girls are progressing too.

19032

It is interesting to note here that, while the girls' genre is now being accepted as a "social document", no such praise was being given to boys' school stories. Instead, the "Stories of Boy School Life" section of 1935 is subtitled "The Mixture as Before" (p812), and begins:

Stories of school life are like peas in the pod; the resemblances being greater than the differences, which are only visible to a close inspection, they all look alike . . . the subject matter of all these tales lacks variety.

It is equally interesting to note that the 1935 edition

also contains a substantial review section on "Independent Children:

Housekeeping and Camping Holidays" (p810), which includes reviews

of Elizabeth Sprigge's Children Alone, Eleanor Graham's Six in

Family [sic], Kitty Barne's The Easter Holidays, Marjorie Fischer's

Street Fair, W.M. Letts' Pomona's Island, Josephine Smith's

Our Island Holiday, Elizabeth Marc's Bush Ragamuffins, Frances

Joyce's Yes, Cousin Joseph, George Wright's Wandering Whipsnaders,

L.W. Bellhouse's The Caravan Children, Lily Jean-Javal's Fortune's

Caravan and Dr Sonnleitner's The Cave Children. The emphasis

in these books lies on adventure in the holidays rather than fun at school,

and the ordered world of the school is replaced with activities arranged

by the children themselves, with little or no adult involvement. Many of

these adventures are "sensational" and portray children heroically,

but because characters of both genders were involved, boys generally take

the lead in what was evidently a more acceptable manner.

19033

A further substantial section is devoted to "Young Riders: Ponies and Other Mounts" (p809), of which the reviewer notes that:

Stories about horses for young people are becoming more and more numerous, and now form a considerable section of the Christmas market. Just as in the school stories, which once held the field unchallenged, incidents such as the theft of a valuable stamp turn up frequently [this particular example applies to boys' school stories], so in these tales we may generally expect a gymkhana, if the scene is laid at home, and often a theft, especially if the surroundings are the Wild West. To be charitable, it must be admitted that the quest of originality is a difficult one, and that in some of these books there are gallant efforts to find it.

19034

While the school story had dominated reading for schoolgirls

for twenty years, its content had now undergone a marked change, then.

Meanwhile there was a choice of genres on offer, and the number of children's

books aimed at either or both sexes was also much wider than ever before.

19035

After more than a year of war, the 7 December 1940 edition of the TLS reflects the impact which wartime shortages was having on the publishing industry, with markedly fewer books being published. Despite this, the choice of girls' books continued to widen, with less than a third of the two columns of books reviewed being school stories. However, the genre is still regarded by the reviewer as being important, and what is perhaps more surprising, as relevant. "Stories of Modern Girls" (pxvii) opens with the comment that:

The schoolgirl of to-day has been called precocious and self-assertive, the sweet simplicity of a happier age being no part of her make-up. Now, however, that perilous days are the portion of every child as well as every grown man and woman in this country, we may be grateful for the poise and self-assurance of the young whose courage and alertness of mind are reflected in the books which our publishers this Christmas offer for schoolgirl reading. Initiative, coolness, and a grasp of present-day problems - all these are to be found in the books that a decade ago would have dealt with Fourth Form intrigue or hockey team rivalries.

19036

It would have been understandable if the genre had been praised because it represented a life without war, but: Angela Brazil's The New School at Scawdale "is an attractive tale of an Australian girl having to adapt herself to English school surroundings. They are evacuated to the country, and among other exciting incidents is that of a whole form being trapped in a flood . . . " Marie Jeanne Lind's Patsy and Norah Mylrea's Lorrie's First Term "are good mystery stories", while:

The Schoolgirl Refugee, by Olive C. Dougan . . . is likely to interest every girl just now, for it is the story of a German girl who, because she had had an English mother, was sent to relatives in England when her brother fell under suspicion for sympathising with rebel Jews and her father was put into a concentration camp for preaching against Nazi injustices. The story develops into a real thriller, with anonymous Swastika warnings and a kidnapping of the plucky young heroine. Miss Dougan has contrived to write about the horrors of life in present-day Germany without undue bitterness, and her characters, whether they are English schoolgirls or German refugees, are all living and likable people. For those who like to give topical books to their young people this would make an admirable choice.

19037

By the end of the war, though, everything had changed.

On 8 December 1945, the TLS article "Children's Books: A list

selected for the Christmas Season" (p586) - which was just two columns

long, reflecting the impact of the long war on the publishing industry

- contained no school stories at all. Following the Second World War, girls'

school stories were neither to recover their popularity, nor the critical

acknowledgement of their importance despite their lack of "literary"

merit, and were to face systematic attempts to consign them to the dustbin

of history. The reasons for this are discussed at the end of the next section![]() .

.

19038

My study of the TLS during the first half of the

twentieth century shows that, rather than the turning point in the genre's

fortunes occurring after the end of the Second World War, the genre was

always a success despite the best efforts of the critics. While the paucity

of girls' books in the first decade of the century was acknowledged by

the critics![]() ,

the huge success of the genre by the end of the First World War was greeted

by a uniform barrage of criticism. Girls' school stories were treated as

merely being an inferior adjunct to the boys' genre, with the term "school

stories" taken to refer to the boys' books, and the genre's "lady"

authors treated with a great lack of respect, as were the books themselves.

,

the huge success of the genre by the end of the First World War was greeted

by a uniform barrage of criticism. Girls' school stories were treated as

merely being an inferior adjunct to the boys' genre, with the term "school

stories" taken to refer to the boys' books, and the genre's "lady"

authors treated with a great lack of respect, as were the books themselves.

19039

This study underlines the fact that it was the readers

themselves who were primarily responsible for the genre's success, demanding

a "stream" of books despite the critical opinions available to

parents and relatives in the shape of the TLS and others. It is

probable, though, that the very lack of respect for the genre which characterised

the reviews prevented parents and teachers from censoring their daughters'

reading; the books were primarily regarded as "harmless, often quite

amusing and seldom very invigorating"![]() .

The greater respect which the critics were to be accorded following the

end of the war meant that they were to become far more influential, and

it is this above all else which is responsible for the genre's changing

fortunes during the post-war period.

.

The greater respect which the critics were to be accorded following the

end of the war meant that they were to become far more influential, and

it is this above all else which is responsible for the genre's changing

fortunes during the post-war period.

19040

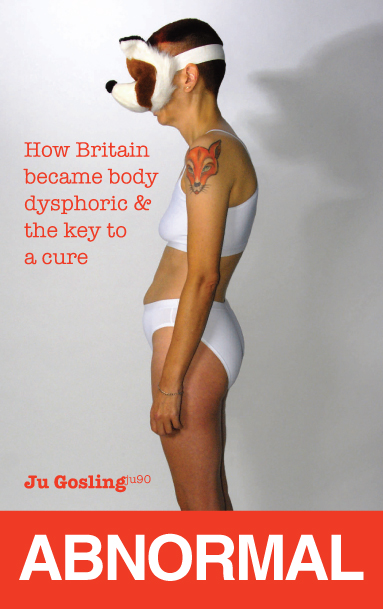

| Dr Ju Gosling aka ju90's ABNORMAL: How Britain became body dysphoric and the key to a cure is available now for just £3.09 for the Kindle or in a limited-edition hardback with full-colour art plates for £20 inc UK postage and packing. |  |