Maud Karpeles was born in West London in 1885, the third child of five. Her father, a banker, was a German immigrant, and both her parents, though not religious, were of Jewish heritage. After she left school, Maud began to volunteer for three or four days a week at Mansfield House. Most of the time she worked for the Invalid Children’s Aid Association, visiting disabled children in East Ham and Barking in their homes, taking them to hospital appointments, advising their parents and so on. However, Maud also volunteered at the Mansfield House Guild of Play, along with her younger sister Helen (1887-1976). The Guild of Play was founded by the Bermondsey University Settlement, and aimed to restore “the art of wholesome play” to children living in extreme poverty. It was common for hundreds of children to attend every night, wearing a cloth hat as a badge of membership. Dancing was central to all Guild activities, and Maud later wrote that at Canning Town she taught the children action-songs and “made-up” dances, including a maypole dance.

Maud was intensely musical, and very interested in the world of the arts. In May 1909 Maud and Helen, then in their early twenties, were in Stratford-upon-Avon to see a Shakespeare play when they heard about a folk dance and song competition that was taking place nearby. Maud and Helen thought folk dancing might be something that the Canning Town children would enjoy learning, and decided to go and watch. The competition’s judges included Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), already well-known as a folk-dance expert, together with Mary Neal (1860-1944). ‘Folk’ was defined as being songs and dances that had been developed by rural communities over generations and passed down by word of mouth, and among other forms encompassed ‘Country’, ‘Morris’ and ‘Sword’ dancing. Often specific to one small community, the songs and dances would have been lost as villagers moved to the cities to find work, were it not for collectors such as Cecil Sharp who wrote them down for the first time. Mary Neal, meanwhile, had been teaching folk dancing to the young seamstresses and other working girls at her Esperance Club in St Pancras since 1905. With the rapid growth in the popularity of folk dancing, the Esperance girls had begun to demonstrate and teach it throughout Britain, and had won a national reputation for their work.

The sisters’ original motive for learning the dances was in order to teach the Canning Town children, but folk dancing soon took over their lives. As well as attending classes themselves, they recruited some friends and founded their own folk dance club, dancing in the drawing room at their home. In 1910, a planned performance for their friends turned into a show for an audience of more than 500, such was the interest in the dance form. Cecil Sharp accompanied the dancers on the piano, and also lectured to the audience about the dances’ history, meaning and benefits. Sharp was very impressed by the Karpeles sisters’ enterprise and high standard of dancing, and invited both of them to join his teaching staff. At the end of 1911, Maud’s club members then came together with others to form the English Folk Dance Society (EFDS). Along with Cecil Sharp, Maud and Helen, founding members included Vaughan Williams, Perceval Lucas, G.J. Wilkinson and George Butterworth. Soon Maud became Sharp’s principal collaborator, as well as a teacher, examiner, competition judge and dance collector in her own right.

Following Sharp’s death in 1924, Maud continued his work collecting and publishing folk songs and dances in Europe and America, as well as working tirelessly for the Society. She was also Sharp’s literary executor, and his biographer (although the first edition of Sharp’s biography was credited solely to A.H. Fox Strangeways). However, by 1938 Maud had been manouevred out of any position of power within the English Folk Dance and Song Society (the two societies had merged in 1932), following a dispute over the copyright to Sharp’s work. Sharp and Neal had agreed on one, highly important issue: although it was a male dance form, women could and should dance Morris in order to keep it alive. However, Douglas Kennedy, Sharp’s successor as Director of the Society from 1925-1961 — and husband of Maud’s sister Helen — violently disagreed. Often at loggerheads with Maud, Kennedy even went to the lengths of banning women from the summer schools unless they could bring a male partner with them. From then on, Maud was mocked as a spinster. It is possible that the growing anti-Semitism throughout Europe also played a role in Maud being ousted from power. The most outspoken critic of women’s involvement with ‘male’ dance forms like Morris and Sword was Rolf Gardiner (1902-1971), who was also an enthusiastic Fascist. Maud, meanwhile, was a democrat and a committed internationalist, as well as a strong advocate of women’s dancing.

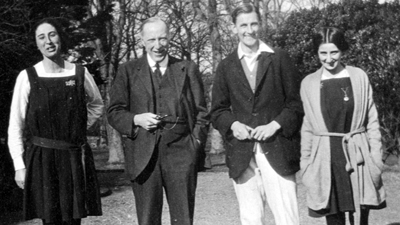

After the end of the Second World War, Maud specialized in folk music rather than dancing. Having been instrumental in founding the international folk movement — the first International Festival took place in London in 1935 — in 1947 Maud helped to found the International Folk Music Council. She continued to work tirelessly and organized folk events around the world until her 90th year, eventually organizing helpers to meet her with a wheelchair when she arrived at a station or airport as well. Canning Town can be proud. The Kinora Films: These films from 1912 are the earliest known example of English folk dance on film. They feature Maud and Helen Karpeles dancing alone and with Cecil Sharp and George Butterworth. Butterworth was a co-founder of the English Folk Dance Society, and but for his death during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, he would have been Sharp's successor rather than Douglas Kennedy.

All photographs of the Folk Dance Summer School and Maud Karpeles are the property of the English Folk Dance and Song Society and should not be reproduced without their permission. The sketch comes from the Musical Times. Text © Ju Gosling aka ju90 2010

|

As

soon as they saw the dancing, Maud and Helen were hooked. That September,

Sharp founded a folk dance school at Chelsea Physical Training College,

and Maud and Helen attended weekly classes. It is hard to imagine today

how daring and liberating it must have felt for the women students to

dance in gym tunics, in a world where women still wore ankle-length

dresses for everything else and where other forms of dance were excessively

formal.

As

soon as they saw the dancing, Maud and Helen were hooked. That September,

Sharp founded a folk dance school at Chelsea Physical Training College,

and Maud and Helen attended weekly classes. It is hard to imagine today

how daring and liberating it must have felt for the women students to

dance in gym tunics, in a world where women still wore ankle-length

dresses for everything else and where other forms of dance were excessively

formal.

Having

lost her position with the Society, Maud turned instead to helping to

resettle child refugees from Europe. When war began in 1939, she founded

a Refugee Musicians’ Committee, as well as working with the Red

Cross and the Christian Council for Refugees, and, briefly, working

on a production line making radios for the Navy.

Having

lost her position with the Society, Maud turned instead to helping to

resettle child refugees from Europe. When war began in 1939, she founded

a Refugee Musicians’ Committee, as well as working with the Red

Cross and the Christian Council for Refugees, and, briefly, working

on a production line making radios for the Navy.