Blue Rosemary, green Myonie, both gazed enthralled up at Rachel, who, in her white working gown, sat on a low chair, bending forward and talking earnestly. . .

"And what happened next?" Myonie whispered.

"Go on, Rachel!" Rosemary gave an excited wriggle.

(Elsie J. Oxenham, A Dancer From the Abbey, Collins, 1953, p191)

Some of my earliest memories are of stories. As a toddler

I loved to have stories told or read to me, and learned many of the lines

by heart. I can still remember chanting the immortal words from one favourite

over and over again: "with a flip and a flop and a terrible THUD,

all of the washing fell down in the MUD!" This oral story-telling

tradition continued until I was in my teens. My father was a wonderful

storyteller, and had the ability to make up stories in whatever genre my

sister and brother and I were reading at the time. My interest in stories

told in both words and pictures (he was also a talented draughtsman and

cartoonist) was stimulated by his example.

for1

It was my mother, though,

who taught me to read and write in the mid-1960s, when I was three or thereabouts.

She used a "magic slate" (greaseproof paper over a black background,

written on with a wooden stick), and, after teaching me my capitals, she announced

that I must learn the "small letters". I gleefully demonstrated that

I could write very small capitals indeed, but soon, crestfallen, I was being

taught about upper and lower cases. Learning to read quickly followed. My first

book was from the "Ladybird" series of primers, and I received it

with disgust. In my opinion, books were supposed to be big and fat with lots

of pages: this book was small and thin; and, as all of the pages were stuck

together, gave me the impression of only containing one page. I ran over the

road to let my Great Aunt commiserate with me, and the book opened up in her

hands.

for2

I was about six, though, before I discovered the real

magic of reading to myself. I was in hospital, a common occurrence during

my early life, and had been given a slim volume of "Brer Rabbit"

stories (written, I now suspect, by Enid Blyton). Bored by the hospital

regime, I started reading them to myself, and the stories flowed and came

alive in a never-to-be-forgotten moment. From then on I was hooked, reading

the back of the cornflakes packet if nothing else was available. I joined

the local library, and before my primary school years were ended had been

awarded an Essex County Libraries "good reader" badge and an

adult library ticket. I also read my parents' books, trying to avoid detection

and censorship by my mother - Hardy's Jude the Obscure is the one

which I remember "losing" halfway through with the most regret.

I had books, too, of my own. I will always remember my father giving me

the first of Enid Blyton's "Famous Five" series, Five on a

Treasure Island, when I was ill in bed at home at about the age of

eight. I loved its firm white pages, its glossy dustwrapper, its smell

. . . I had a terrible headache, but I couldn't stop reading it. I also

haunted jumble sales, beginning my habit of collecting secondhand books

even then.

for3

Why do I begin here? It is to reassure the reader that,

despite the presentation of this work in electronic form, I am a book lover,

as are the girls's school story readers who have participated in this research.

At the end of the millennium, it seems fitting to look more closely at

a genre which has been the most popular reading choice across generations

of twentieth-century British girls; and which forefronts that twentieth-century

British phenomenon, access to education for girls - particularly so, since

this choice has been made despite the disapproval of critics, teachers,

librarians and parents, and since girls have chosen to return to the books

again and again. It also seems fitting, at the end of a century when literacy

in the UK appears to have peaked, and which has been marked by a revolution

in communications technologies, to explore the future of writing and reading

in an electronic age. But while attempting to demonstrate the benefits

of the ebook (a full discussion of the electronic book can be found in

The E-Book and the Future of Reading![]() ),

Virtual Worlds of Girls also celebrates printed books and reading.

The pages may be virtual

),

Virtual Worlds of Girls also celebrates printed books and reading.

The pages may be virtual![]() ;

the means of reading electronic; the story told by images as well as print

- but it is still a book (or rather a collection of books) at heart

;

the means of reading electronic; the story told by images as well as print

- but it is still a book (or rather a collection of books) at heart![]() ,

and books are at its heart.

,

and books are at its heart.

for4

The Virtual Worlds of Girls hypertext cluster explores

the roles which printed stories play in readers' lives: from the development

of the psyche and the pleasure given by reading and re-reading; to collecting

and owning books and the friendship networks which can result; to the wider

historical significance of these phenomena. It also tells some stories

of my life: of my own schooldays![]() ;

and of my experiences as a disabled researcher

;

and of my experiences as a disabled researcher![]() while carrying out this work. As an artist-academic, I am concerned with

the ways in which stories are told and received, the meaning which this

generates and the significance which this has for us. Stories mediate between

the world of our imagination and the world which we experience externally,

and transform these worlds in the process.

while carrying out this work. As an artist-academic, I am concerned with

the ways in which stories are told and received, the meaning which this

generates and the significance which this has for us. Stories mediate between

the world of our imagination and the world which we experience externally,

and transform these worlds in the process.

for5

A story, whichever medium or media is used to tell it,

delivers an idea or a message, makes a point, teaches us a way of looking

at the world - it shows us the world virtually, in degrees of representation

which range from the apparently faithful to the purely symbolic, with a

focus which ranges from narrow to wide, but always saying something about

some aspect of the human condition. Just as change must occur within the

virtual world of a narrative story in order to satisfy the demands of story

structure, so must all stories effect some change, however slight, in the

reader/viewer, leaving them with heightened, if often unconscious awareness

when they return to real life. The storyteller speaks directly to the unconscious

as well as to the imagination, using different techniques which require

various levels of physical and creative skills depending on the medium

or media being used. They present their story with varying degrees of mastery,

which is at its most sublime when the ideas it contains are profound, yet

delivered subtly and in a convincing manner. Stories are as close as we

come to experiencing a shared, virtual reality.

for6

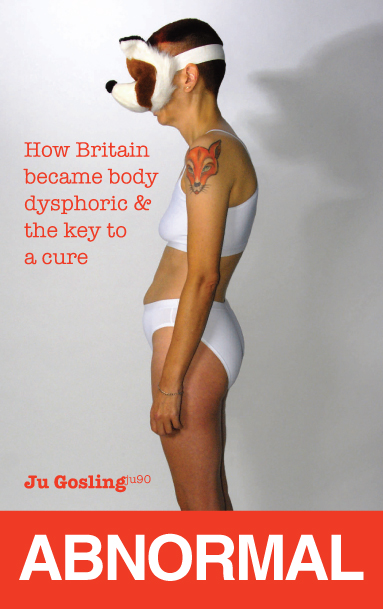

| Dr Ju Gosling aka ju90's ABNORMAL: How Britain became body dysphoric and the key to a cure is available now for just £3.09 for the Kindle or in a limited-edition hardback with full-colour art plates for £20 inc UK postage and packing. |  |