"Oh!" said Jen again, when they had entered

by big iron gates, and the great house at the end of the drive came into

sight. She looked at Joy. "What a lot of things you've got!"

she said, without a twinge of envy, but in frank admiration.

Joy laughed. "Have I? Such as -?"

"It's all yours, isn't it? All the miles of gardens, and this gorgeous

house? And then being Queen - and the girls say you're a musical genius

- and you're pretty."

(Elsie J. Oxenham, The Girls of the Abbey School, 1921, p28)

My parents provided a classic example of British class

mobility in the twentieth century, combining upwardly mobile working-class

Londoner with downwardly mobile upper-class countrysider in a family which

nonetheless failed to adopt middle-class norms and values successfully.

hom1

My father

was born in 1928, the son of a "gentleman farmer". He grew up on the

family farm in Suffolk, and, like his elder brother attended Ipswich School,

a minor public school. But whereas my uncle went on to Queen's College, Cambridge

and into the RAF before qualifying as a surgeon at a famous teaching hospital

in London, my father left school in 1942 at the age of 14 to spend the rest

of the war working on the farm, with little regard for formal education and

in the belief that farming would be his career. However, their father developed

a brain tumour in the mid-1950s, as a result of which he lost most of the family

assets on the stock market before deciding to sell the farm and to move to a

town house in nearby Ipswich. My uncle, having married a Scottish nurse, emigrated

with his family to Canada, while my father accompanied his parents to Ipswich

and looked after them, taking out his frustrations in a social life which continued

to revolve around the Young Farmers' Club (whatever the impression given by

the name, by all accounts they were a wild set).

hom2

Meanwhile

my maternal grandfather was born the youngest of seven children in 1900, his

father having died before his birth. He grew up in a tenement in Lambeth, South

London, sharing an outside tap with dozens of other families. His mother worked

as a seamstress, leaving my grandfather to the care of the other children, and

at the age of two he narrowly escaped death when he fell into the fire and was

seriously burned. Later his two eldest brothers were "rescued" from

the family home by the Dr Barnado's charity and sent to work in Canada, plunging

the family deeper into poverty, but my grandfather eventually became an apprentice

printworker in his early teens, a much sought-after position. To his lifelong

regret, however, my grandfather was removed and put into a candle factory by

his mother when the First World War began; with his remaining brother away fighting,

the family was unable to manage on an apprentice's wages. Later my grandfather

joined the army, missing the action only because he went on to take further

training; he was one of the first soldiers to be sent to France following the

Armistice. He then served in Germany and India, where the height of his career

was arranging the entertainments, including performing himself on the banjo.

Meanwhile

my maternal grandfather was born the youngest of seven children in 1900, his

father having died before his birth. He grew up in a tenement in Lambeth, South

London, sharing an outside tap with dozens of other families. His mother worked

as a seamstress, leaving my grandfather to the care of the other children, and

at the age of two he narrowly escaped death when he fell into the fire and was

seriously burned. Later his two eldest brothers were "rescued" from

the family home by the Dr Barnado's charity and sent to work in Canada, plunging

the family deeper into poverty, but my grandfather eventually became an apprentice

printworker in his early teens, a much sought-after position. To his lifelong

regret, however, my grandfather was removed and put into a candle factory by

his mother when the First World War began; with his remaining brother away fighting,

the family was unable to manage on an apprentice's wages. Later my grandfather

joined the army, missing the action only because he went on to take further

training; he was one of the first soldiers to be sent to France following the

Armistice. He then served in Germany and India, where the height of his career

was arranging the entertainments, including performing himself on the banjo.

hom3

My

grandfather returned to London in the late 1920s, where, after his mother remarried,

he married a woman he had known in his teenage years, who was also a seamstress.

Despite the Depression, his army background was enough to gain him, first, a

position as a London bus conductor, and then a rented house of his own in a

local authority owned "garden estate" in south London which was completed

in the early 1930s. His family were the first to live in a house which included

a sitting room, dining room, three bedrooms and, wonder of wonders, an inside

bathroom. My mother was born in 1934, the middle child, sandwiched between a

brother who was bright enough to win a free place at a grammar school and a

sister who was good at sport. The family survived the war together - as did

the house, despite some near-misses - but shortly afterwards my grandmother

developed breast cancer and died. As my mother points out, there was no state

and little charitable help available then for widowed fathers, despite there

being many schemes for widowed mothers, and my grandfather found it difficult

to manage. Despite having at least one opportunity to do so, he never remarried,

but later found an outlet by becoming active in the local Labour Party and Transport

and General Workers' Union - which meant that he spent even less time at home.

My

grandfather returned to London in the late 1920s, where, after his mother remarried,

he married a woman he had known in his teenage years, who was also a seamstress.

Despite the Depression, his army background was enough to gain him, first, a

position as a London bus conductor, and then a rented house of his own in a

local authority owned "garden estate" in south London which was completed

in the early 1930s. His family were the first to live in a house which included

a sitting room, dining room, three bedrooms and, wonder of wonders, an inside

bathroom. My mother was born in 1934, the middle child, sandwiched between a

brother who was bright enough to win a free place at a grammar school and a

sister who was good at sport. The family survived the war together - as did

the house, despite some near-misses - but shortly afterwards my grandmother

developed breast cancer and died. As my mother points out, there was no state

and little charitable help available then for widowed fathers, despite there

being many schemes for widowed mothers, and my grandfather found it difficult

to manage. Despite having at least one opportunity to do so, he never remarried,

but later found an outlet by becoming active in the local Labour Party and Transport

and General Workers' Union - which meant that he spent even less time at home.

hom4

The remainder of my mother's childhood

was deprived both emotionally and financially, with her main sources of

comfort being the local mission hall and the Girl Guide company. Despite

being ambitious, she was unable to afford to stay at school beyond the

age of sixteen, so worked for two years in Foyle's Bookshop, Charing Cross

Road before being accepted for nurse training at St Helier Hospital in

South London. By the time that my parents met at a dance in the late 1950s,

she had qualified as a State Registered Nurse and a State Registered Midwife

and had left London behind her, working as a midwife in Ipswich. My parents'

relationship quickly progressed, but my father was in no position financially

to marry. His father had died, and the will required both him and his mother

to leave their Ipswich home. There was little capital left, and without

qualifications my father found it hard to get work, with brief spells as

a draughtsman and a van driver breaking up longer periods of unemployment.

hom5

My

paternal grandmother came from a middle-class East Anglian family, and her unmarried

sister (pictured), had moved soon after the Second World War to a small seaside

town in Essex on the East coast of England. "Auntie" had adopted a

daughter, who was a teenager by the early 1960s, and made a living by providing

lodgings for girls attending a nearby private school (this was defunct by the

end of the 1960s); and in the holidays for small children taking a seaside holiday

accompanied by their nannies and for actors appearing at the local summer repertory

theatre, based in the Women's Institute hall.

My

paternal grandmother came from a middle-class East Anglian family, and her unmarried

sister (pictured), had moved soon after the Second World War to a small seaside

town in Essex on the East coast of England. "Auntie" had adopted a

daughter, who was a teenager by the early 1960s, and made a living by providing

lodgings for girls attending a nearby private school (this was defunct by the

end of the 1960s); and in the holidays for small children taking a seaside holiday

accompanied by their nannies and for actors appearing at the local summer repertory

theatre, based in the Women's Institute hall.

hom6

My

grandmother used the last of the family money to buy a detached house in

the same "upper" avenue as her sister, and at the end of the

1950s she moved there, accompanied by my father. My grandmother must have

had mixed feelings about my mother, but eventually realised that offering

them both a home so that my parents could afford to marry was the surest

way to keep my father, on whom she had relied since he was a teenager.

The marriage duly took place at the local Registry Office - there was no

money for a church ceremony, although my mother at least would have preferred

one - and my father later found work selling insurance door-to-door for

the Co-Operative Insurance Society

My

grandmother used the last of the family money to buy a detached house in

the same "upper" avenue as her sister, and at the end of the

1950s she moved there, accompanied by my father. My grandmother must have

had mixed feelings about my mother, but eventually realised that offering

them both a home so that my parents could afford to marry was the surest

way to keep my father, on whom she had relied since he was a teenager.

The marriage duly took place at the local Registry Office - there was no

money for a church ceremony, although my mother at least would have preferred

one - and my father later found work selling insurance door-to-door for

the Co-Operative Insurance Society![]() .

My mother easily found work at the local maternity hospital, but quickly

became pregnant herself, only to lose the baby in a miscarriage before

giving birth to me in May 1962. My birth came as something of a surprise

to both my parents, since they had been convinced that I would be a boy.

.

My mother easily found work at the local maternity hospital, but quickly

became pregnant herself, only to lose the baby in a miscarriage before

giving birth to me in May 1962. My birth came as something of a surprise

to both my parents, since they had been convinced that I would be a boy.

hom7

I

entered a house which was dominated by old ladies: my grandmother; "Auntie";

and their friends. I was the apple of their collective eye, but my mother was

not so fortunate and found the domestic arrangements very hard to live with,

as well as, unsuprisingly, finding it difficult to form a bond with me in the

circumstances. By the time that my sister arrived in March 1964, though, my

grandmother was content to leave her care to my mother. Meanwhile I enjoyed

sitting on "granny's" lap and waiting until she pretended to go to

sleep to take a chocolate mint from her box; we both pretended, to our mutual

pleasure, that a mouse had eaten it. Perhaps my grandmother's health was declining;

in any case she died in her sleep the following year, shortly before I was three.

Her body was discovered by my infant self; I had been used to going into her

bedroom first thing in the morning, and couldn't understand why Granny wouldn't

wake up. My uncle and his wife, arriving promptly from Canada, signed over their

half of the house to my father in return for removing the remaining family valuables,

and my family continued to live there until the early 1990s, joined by my brother

in April 1967.

I

entered a house which was dominated by old ladies: my grandmother; "Auntie";

and their friends. I was the apple of their collective eye, but my mother was

not so fortunate and found the domestic arrangements very hard to live with,

as well as, unsuprisingly, finding it difficult to form a bond with me in the

circumstances. By the time that my sister arrived in March 1964, though, my

grandmother was content to leave her care to my mother. Meanwhile I enjoyed

sitting on "granny's" lap and waiting until she pretended to go to

sleep to take a chocolate mint from her box; we both pretended, to our mutual

pleasure, that a mouse had eaten it. Perhaps my grandmother's health was declining;

in any case she died in her sleep the following year, shortly before I was three.

Her body was discovered by my infant self; I had been used to going into her

bedroom first thing in the morning, and couldn't understand why Granny wouldn't

wake up. My uncle and his wife, arriving promptly from Canada, signed over their

half of the house to my father in return for removing the remaining family valuables,

and my family continued to live there until the early 1990s, joined by my brother

in April 1967.

hom8

The

house was always marked by its origins as my grandmother's home, being furnished

with the leftovers from the farmhouse which my uncle had rejected as not being

worth shipping. My mother rightly considered us very fortunate, but my siblings

and I remained envious of the south London council house in which my mother's

sister and her family lived, with its modern furnishings and decorations. My

aunt's husband was a master stonemason and she worked part-time as a swimming

teacher, and their income allowed all manner of clothes, outings and holidays

which were beyond my family's means. (The relationship between my family and

my mother's family was always strained: they regarded my father as "a gentleman"

and us as rather snobby; whereas we regarded them with envy as fashionable Londoners.

My father, who was the least snobbish man whom I have ever met, and who was

thoroughly sociable as well as being entertaining, thrived in whatever society

he found himself in, including my mother's family, but the rest of us were not

so fortunate and found the infrequent visits difficult.)

The

house was always marked by its origins as my grandmother's home, being furnished

with the leftovers from the farmhouse which my uncle had rejected as not being

worth shipping. My mother rightly considered us very fortunate, but my siblings

and I remained envious of the south London council house in which my mother's

sister and her family lived, with its modern furnishings and decorations. My

aunt's husband was a master stonemason and she worked part-time as a swimming

teacher, and their income allowed all manner of clothes, outings and holidays

which were beyond my family's means. (The relationship between my family and

my mother's family was always strained: they regarded my father as "a gentleman"

and us as rather snobby; whereas we regarded them with envy as fashionable Londoners.

My father, who was the least snobbish man whom I have ever met, and who was

thoroughly sociable as well as being entertaining, thrived in whatever society

he found himself in, including my mother's family, but the rest of us were not

so fortunate and found the infrequent visits difficult.)

hom9

In comparison to what is taken for granted by most children

in Britain in the late 1990s, there was little domestic technology in our

house - our washing machine had to be pulled out from the wall and attached

to the sink by rubber hoses which frequently flooded; hot water was provided

by a coal-fired boiler; and a tumble dryer was unthought-of luxury. I do

remember a toaster in the 1970s - or at least setting fire to the kitchen

whilst using it - but microwaves were unheard of. We had no record player,

and the only radio station which we could receive without interference

was the pirate Radio Caroline, whose ship was eventually washed up on the

sea wall which bordered the marshes to the south of the town. I did, however,

receive a tape machine from my parents one Christmas in the early 1970s,

and this I used to play music tapes which I had recorded from the radio

as well as to create spoof programmes with my father. And I will always

remember when my father brought home his first pocket calculator, a Sinclair.

This cost what seemed to us an enormous amount of money and performed only

the most basic functions, but we regarded it with amazement.

hom10

In terms of television, we had an old black-and-white

set which could only receive ITV; when we hired a colour television at

the end of my primary school years which could also receive the BBC it

was a very special day. I loved to watch television, but unfortunately

my mother believed that it was a waste of our time, and often removed the

aerial to prevent us from switching it on behind her back or to punish

us. She would frequently point out that we "could watch all the television

you want to when you're grown up"; she also, despite encouraging me

to read, disliked my reading "rubbish" such as girls' school

stories. (My mother, having somehow assimilated many of the values of the

academy, regarded all popular culture as "low". No doubt, though,

her attitude was a factor in my first choosing to study film and television

as an undergraduate and then going on to work in these fields, as well

as choosing girls' school stories as a subject for postgraduate research.![]() )

)

hom11

My

home town had been a popular Edwardian resort for the upper middle classes,

partly because it was situated less than a hundred miles from London and was

easily reached by rail. In the 1960s it still clung to its former reputation,

resisting all attempts at modernisation. There were byelaws banning anything

and everything thought to be "common", from public houses to fish

and chip shops, from cycling on the promenades to eating on the greensward,

from selling icecream or gifts on the beach to playing a radio in public. Holiday

visitors were necessarily of a staid disposition, and many were Londoners with

second homes in the town. Citizens were divided into two groups: those who lived

within the old town "inside the gates"; and the less fortunate who

lived "outside the gates" in more modern homes. The boundary was created

by the railway line which ran about half a mile parallel to the coast, the rickety

wooden "gates" closing off the level crossing when trains ran through.

In retrospect the attitude of the townspeople seems almost defiant given the

egalitarianism of the 1960s and the new glamour of the working classes; it certainly

fuelled my cousins' beliefs that my family were "snobs".

hom12

The origins of the town

lay in Saxon times, but in the past millennium the coastline had been heavily

eroded, and, like much of the East Anglian coast, the town was now surrounded

by flat, marshy countryside which frequently flooded. A tiny church which had

been listed in the Domesday Book now stood close to the beach, and the low clay

cliffs continued to crumble during my childhood, resulting in at least one fatal

accident before they were shored up at the end of the 1960s. The beach itself

consisted of the stereotypical miles of golden sands divided by wooden breakwaters,

although the picture was often somewhat spoilt by the sewage pollution from

a local outfall pipe. The past erosion of the cliffs also meant that at low

tide the unwary risked slipping on patches of clay when they ventured beyond

the breakwaters which prevented the sandy beach from being washed away by the

tide.

hom13

A concrete promenade divided the beach from the cliffs,

and this was lined with wooden beach huts. Many of them dated back to the

1920s, until a storm swept hundreds away in the mid-1970s and they were

replaced by modern constructions. (Unfortunately a second storm later the

same winter destroyed many of the replacements, although there have been

no similar occurrences since.) These huts could be bought or hired, with

land rent paid to the local council. They provided popular bases for days

on the beach, but inevitably a byelaw prevented anyone from staying in

them at night. At the top of the cliffs, a greensward divided the beach

from the old town. This part of the town consisted largely of one "avenue"

of shops, with five "avenues" of houses running at right angles

from the cliffs to the railway line. These avenues were bisected by a road

running parallel to the coast, with the "upper" avenues containing

smaller and less desirable houses. To the north, a jumble of smaller roads

and lanes led to the next town, an overgrown fishing village.

hom14

Despite the town's upper-class

pretensions, most of its citizens were solidly non-intellectual middle class,

including many with working-class origins. At the beginning of the 1960s there

were still many elderly residents with upper-middle-class origins - the town

was often laughed at in the surrounding area as "the last bastion of the

British Empire" - but by the end of the decade most of these residents

had died, to be replaced by other retired people. Meanwhile the majority of

men of working age originated from London and commuted back to jobs in the City.

There were few local jobs apart from in the shops, and these were mostly staffed

by women. For most of the week, then, the town was occupied only by women, children

and the elderly. Later, a road sign outside Colchester was to become famous

when it was graffitied to read "Harwich for the Continent; [my home town]

for the incontinent" (a sign of which I was uncomfortably aware,

since I had poor bladder control during my childhood).

hom15

With

public houses banned, the only places to socialise and drink were the bars of

the decaying hotels, although men could also join the "Memorial Club",

which was I think dedicated to those locals who had been killed in the two World

Wars. My father never became a member - he rarely drank alcohol, mostly due

to lack of money - but later my grandfather was to enjoy a drink there when

he came to stay with us. The town did have a golf club, tennis club and cricket

club which provided sports and social facilities and activities, but the membership

of these was almost entirely composed of commuters and their families, together

with the people who owned summer homes in the town. Probably deliberately, the

membership fees were set too high to allow families like mine to belong, although

- perhaps as a result of a "pools" win - we spent one blissful summer

with swimming membership of the tennis club (swimming in the sea was considered

to be very infra dig in the first age of the swimming pool).

With

public houses banned, the only places to socialise and drink were the bars of

the decaying hotels, although men could also join the "Memorial Club",

which was I think dedicated to those locals who had been killed in the two World

Wars. My father never became a member - he rarely drank alcohol, mostly due

to lack of money - but later my grandfather was to enjoy a drink there when

he came to stay with us. The town did have a golf club, tennis club and cricket

club which provided sports and social facilities and activities, but the membership

of these was almost entirely composed of commuters and their families, together

with the people who owned summer homes in the town. Probably deliberately, the

membership fees were set too high to allow families like mine to belong, although

- perhaps as a result of a "pools" win - we spent one blissful summer

with swimming membership of the tennis club (swimming in the sea was considered

to be very infra dig in the first age of the swimming pool).

hom16

Unsurprisingly, the townspeople were heavily conventional

and solidly Conservative (with both a large and a small "c").

Almost all were white, although there was one mixed-race boy at my primary

school and an Afro-Caribbean girl at a neighbouring school. In my last

year at primary school, in 1972, a Ugandan Asian family moved in temporarily,

but later left for a permanent home elsewhere. Racism was generally covert,

but a half-German girl suffered considerable abuse as a "Nazi".

My mother, who had dark hair and eyes and deeply tanned olive skin (probably

inherited from my maternal grandmother, of whom we know little), and my

brother, who had inherited the least English side of both my parents' looks,

were viewed with suspicion, and my brother was often called "meat

face" at primary school. (With paler skin and green eyes, it was only

many years later, when a girlfriend referred to my "exotic" looks,

that I realised my parents' mixed blood had always affected both my appearance

and attitudes to me too.) I certainly felt that many of my parents' friends

in the town looked down on my mother, partly because of her working-class

London background - even if theirs was similar, they now enjoyed a far

higher standard of living than my own family - and partly because of her

complexion.

hom17

The social upheavals of the 1960s largely passed us by,

although there were once exciting rumours about a "pop festival"

held in the neighbouring countryside. Instead, the town was heavily religious,

with the Church of England, Catholic Church, Methodist Church, Free Church,

Gospel Hall and Christian Science all represented. (In addition to these,

pentacles often appeared on the beach.) My sister, brother and myself attended

the Church of England's Sunday School, although my family's attendance

at the actual church services was sporadic (it was only in retrospect that

I realised why my parents liked an hour to themselves on Sundays). Later,

in the mid-1970s, my mother and sister attended the Free Church, which

was similar to the better-known Baptist Church (although I have more recently

seen it described in a national newspaper as a "cult"). My mother

found that these services reminded her of the London mission hall where

she had attended services as a child, while my sister was tempted by the

fact that the Free Church operated the town's only youth club.

hom18

Unlike my sister, I decided that the benefits of belonging

to a youth club were not worth the price of attending church every Sunday.

However, in the summer holidays the churches were further augmented by

the Children's Special Service Mission (CSSM), who conducted services and

social activities on the beach. The mission workers were students and I

joined in their events happily, becoming freshly converted to Christianity

every August and lapsing every September. In the early 1990s, when I watched

the repeated BBC adaptation of Jeanette Winterson's Oranges are not

the only fruit (Pandora, London, 1985), I realised that I knew the

words and tunes to every religious song portrayed in it as a result of

the heavily evangelical atmosphere of my childhood. Like Winterson, I left

as soon as I could, taking an au pair's job in Paris a few days after leaving

school and a few weeks after my eighteenth birthday. My mother remained

in the town, my sister returned to it and my brother now lives close by,

but I continue to find it too oppressive to remain there longer than overnight.

hom19

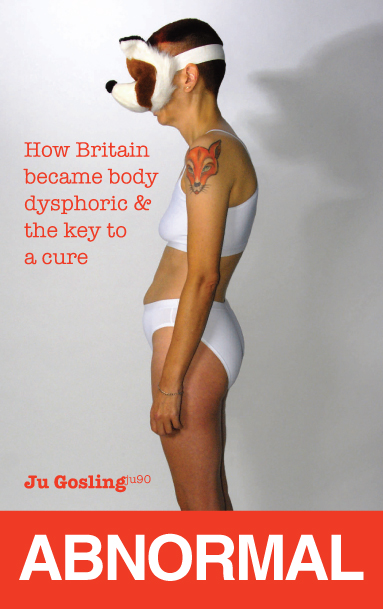

| Dr Ju Gosling aka ju90's ABNORMAL: How Britain became body dysphoric and the key to a cure is available now for just £3.09 for the Kindle or in a limited-edition hardback with full-colour art plates for £20 inc UK postage and packing. |  |