"Yes, Miss Parker," said Belinda, meekly, and

began to make a little sketch of the teacher on her blotting-pad. . .

Nearly every girl in the class now had a neat little sketch of Mam'zelle

marking her place in her French grammar. It was the ambition of the class

to have, as a marker, caricatures of all the mistresses taking their different

classes - Miss Carton for their history books, Miss Grayling for the scripture

exercise books, Mr Young for the school song book and so on.

(Enid Blyton, Second Form at Malory Towers, Methuen, 1947, pp28-9)

Ronald

Searle, creator of St Trinian's, was born in Cambridge in 1920

Ronald

Searle, creator of St Trinian's, was born in Cambridge in 1920![]() .

After leaving school at the age of fourteen, he took night classes at the

Cambridge School of Art (which overlooked his sister Olive's school playground,

a possible source of inspiration). In order to pay for his tuition, he

worked first as a solicitor's clerk and then, after a period of unemployment,

as a parcel-packer and later as a clerk at the Co-op. At the age of fifteen,

when he started working for the Co-op, he became the resident cartoonist

on the Cambridge Daily News, and at sixteen he also began contributing

to the student magazine, The Granta. In September 1938, at the age

of eighteen, he was granted a year's scholarship by the local Education

Committee which allowed him to study full-time at the School of Art, although

he continued to work for the CDN, as it was known locally. Then,

in April 1939, at the age of nineteen, Searle joined the Territorial Army

as an Architectural Draughtsman in the Royal Engineers with the rank of

Sapper, and left the School of Art in the summer after scraping through

the Ministry of Education's Drawing Diploma's examination with 42% (the

pass mark being 40%).

.

After leaving school at the age of fourteen, he took night classes at the

Cambridge School of Art (which overlooked his sister Olive's school playground,

a possible source of inspiration). In order to pay for his tuition, he

worked first as a solicitor's clerk and then, after a period of unemployment,

as a parcel-packer and later as a clerk at the Co-op. At the age of fifteen,

when he started working for the Co-op, he became the resident cartoonist

on the Cambridge Daily News, and at sixteen he also began contributing

to the student magazine, The Granta. In September 1938, at the age

of eighteen, he was granted a year's scholarship by the local Education

Committee which allowed him to study full-time at the School of Art, although

he continued to work for the CDN, as it was known locally. Then,

in April 1939, at the age of nineteen, Searle joined the Territorial Army

as an Architectural Draughtsman in the Royal Engineers with the rank of

Sapper, and left the School of Art in the summer after scraping through

the Ministry of Education's Drawing Diploma's examination with 42% (the

pass mark being 40%).

ron1

Searle was soon called up into the regular army - on 1 September 1939 - and after a few week's training was stationed in Norfolk. That month, November, he saw his first drawing published in a national paper: an illustration for a short story in the Daily Express. In January 1941 his work was included in an exhibition of wartime artwork by members of H.M. Forces stationed in East Anglia at Norwich Castle, but by then Searle had left for the village of Kirkcudbright in Scotland, which happened to be an artist's community. This posting was to affect the rest of his career.

One of his most welcome ports of call was the home of

the Johnston family . . . One day, as a purely domestic joke, he made a

drawing to please the two schoolgirl daughters, Cécilé and

Pat, who attended an Academy for Young Ladies in Dalkeith Road, Edinburgh

(temporarily evacuated to the west coast). The name of their school was

- St Trinnean's.

It's success at the hospitable tea table was such that he was encouraged

to include it with a small number of cartoons he was hopefully submitting

to a monthly magazine.

The address he wrote on the label was: Miss Kaye Webb, Assistant Editor,

LILLIPUT . . . and the date on the registration slip, which he still has,

was 13 July 1941.![]()

ron2

Lilliput accepted the cartoon![]() ,

and it was published in October 1941. It shows a group of schoolgirls gazing

bemusedly at an official noticeboard, bare flesh showing between the tops

of their stockings and their gym slips. The cartoon's caption, slightly

reworded by Webb, reads: "Owing to the international situation, the

match with St Trinian's has been postponed." (In fact, of course,

the girls must have belonged to another school, but the drawing is always

known as the first St Trinian's cartoon.) Searle, however, had been posted

abroad before publication, arriving in Singapore in January 1942. By the

end of the month the British forces had withdrawn from Malaya to the island,

but this was not enough to stop the Japanese from invading, which they

did on 9 February 1942. On 13 February, under enemy fire, Searle found

a copy of the October issue of Lilliput amongst debris in a Singapore

street, and saw his cartoon in print for the first time. Two days later

the British forces surrendered, and Searle was listed as "missing",

his career also postponed "owing to the international situation".

No more was heard of him for almost two years, until the Red Cross finally

informed his family that he was alive on 29 December 1943.

,

and it was published in October 1941. It shows a group of schoolgirls gazing

bemusedly at an official noticeboard, bare flesh showing between the tops

of their stockings and their gym slips. The cartoon's caption, slightly

reworded by Webb, reads: "Owing to the international situation, the

match with St Trinian's has been postponed." (In fact, of course,

the girls must have belonged to another school, but the drawing is always

known as the first St Trinian's cartoon.) Searle, however, had been posted

abroad before publication, arriving in Singapore in January 1942. By the

end of the month the British forces had withdrawn from Malaya to the island,

but this was not enough to stop the Japanese from invading, which they

did on 9 February 1942. On 13 February, under enemy fire, Searle found

a copy of the October issue of Lilliput amongst debris in a Singapore

street, and saw his cartoon in print for the first time. Two days later

the British forces surrendered, and Searle was listed as "missing",

his career also postponed "owing to the international situation".

No more was heard of him for almost two years, until the Red Cross finally

informed his family that he was alive on 29 December 1943.

ron3

Searle, though, continued cartooning and drawing secretly

during his time as a prisoner of war, recording many of the events which

took place. After a time in Changi prison camp, he eventually he fell foul

of the British authorities with his contributions to The Survivor,

a radical magazine circulated secretly and banned by the British on his

23rd birthday, 3 March 1943. As a consequence, Searle was sent to work

as a labourer on the Siam-Burma railway, where he suffered continual bouts

of malaria. He finally entered the camp hospital after an attack by the

guards on one of his hands, by which time he was also suffering from beri-beri,

ulcers and skin disease. In September 1943, he was paralysed by a blow

from a guard's pick-axe which penetrated his back as far as the spine,

and was taken to the sick lines weighing around seven stone.

ron4

The railway was completed on 25 October 1943, but Searle

was too ill to be moved to Singapore. He was eventually transported to

the Sime Road camp near Singapore race course in December 1943, when his

malaria immediately recurred. However, he recovered enough to design and

perform in the prisoners' shows, and on 4 May 1944 was transferred to Changi

Gaol, a modern prison built by the British eight years beforehand. Originally

intended for eight hundred prisoners, ten thousand men were now incarcerated

there, with Searle living in a cell which contained two hundred men. Despite

the hardships, though, Searle continued to draw, contributing to a new

magazine, The Exile, as well as designing shows and recording camp

activities. The Japanese were aware of his activities, and in 1945 he spent

three months drawing murals at a beach villa and officers' club before

the prison administrator, an artist who admired Searle, was abruptly transferred.

By 10 August 1945 Searle's health had became so poor that he had to have

an ulcer on his leg surgically excavated, but on 15 August 1945 the ceasefire

was declared, and on 27 September he began the journey home, arriving in

Liverpool on 24 October 1945.

ron5

Searle lost no time in picking up his career where it had left off. In November 1945, as Kaye Webb describes, Searle:

walked into our offices bearing a neat folder containing

seventy-two cartoons. They were drawn in faded brown ink, on stained and

yellowing paper. Some of them were crumpled. Most of them had survived

burial in the jungle undergrowth or under disease-ridden mattresses, where

the Japanese would be unwilling to search. Among them were the second and

third St Trinian's drawings. We asked him for more and published them every

month for the next three years.![]()

Over the five years which separated the first and second

St Trinian's cartoons, the content had undergone a fundamental change.

If this had not been so, it is doubtful whether Searle would have continued

drawing them at all, since there was no real hint in the first cartoon

of what was to become the joke underlying the rest. In contrast to the

first cartoon, the second to be published (it was the third to be drawn,

in Changi Gaol) shows a classroom full of grinning schoolgirls, all with

their hands at their sides, being addressed by a Victorian-looking schoolmistress:

"Hand up the girl who burnt down the East wing last night."![]() Another cartoon which was first published in 1946 shows three schoolgirls,

hockey sticks in hands, gathered around a tree from which a schoolmistress

- also Victorian in appearance and still holding a cane - is hanging: "Well

that's O.K. - now for old 'Stinks'."

Another cartoon which was first published in 1946 shows three schoolgirls,

hockey sticks in hands, gathered around a tree from which a schoolmistress

- also Victorian in appearance and still holding a cane - is hanging: "Well

that's O.K. - now for old 'Stinks'."![]()

ron6

The joke was that, contrary to the popular image of the

quiet, well-behaved, "honourable" British boarding-school girl

which had dominated from the beginning of the century until the Second

World War, the girls were in fact violent, even demonic, gin-swigging,

cigar-smoking and out of control. Rather than being "innocent"

and worthy of respect - the pre-war ideal - the girls were worldly wise

and to be feared. The fear of girls' schools and school stories as promoting

women's independence and lesbianism had, of course, been the motivating

factor for attacks on the genre from as early as 1915. While the post-war

critics became more overt in their attempts to repress the genre, the post-war

parodists became more overt in revealing the reasons for these fears. That

these fears were widespread can be seen in the fact that St Trinian's quickly

became "a new National joke"![]() ;

"a term of national reference, so that but to say 'St Trinian's' was

to conjure up a whole world"

;

"a term of national reference, so that but to say 'St Trinian's' was

to conjure up a whole world"![]() ;

"The Times has referred more than once to 'Trinianism' confident

that this will be immediately comprehensible to its readers"

;

"The Times has referred more than once to 'Trinianism' confident

that this will be immediately comprehensible to its readers"![]() .

.

ron7

Webb, with whom Searle began an affair in 1946, has pointed out that:

it was inevitable that the débacle [Searle] had

just witnessed, the atmosphere of cruelty and the smell of death in which

he and his companions existed for . . . four years, should permeate his

drawings so that the next two schoolgirl jokes took on their first flavour

of violence. It hardly seems necessary to mention that Searle does not

really think of schoolgirls as murderous little horrors. But unconsciously

he was seeking to reduce horror into a comprehensible and somehow palatable

form.![]()

It is probable, too, that the public's experience and/or

awareness of wartime cruelties and horrors is another reason why the cartoons

were so well-received.

ron8

The following year, 1947, when Webb gave birth to a twin

son and daughter (the couple later married, in 1948), the gin-swigging,

cigar-smoking aspect of the girls emerged. For example, one cartoon shows

a group of four girls, two with hockey sticks and all wearing their boater

hats, sitting on their dormitory beds having a drink: "My God - she's

put water with it again!" ![]() Another

features a lone schoolgirl, also complete with hat, sitting in a classroom

writing the "lines": "I must not smoke cigars during prayers.

I must not smoke cigars during prayers . . . " (This was later reproduced

with the word "pot" replacing "cigars"

Another

features a lone schoolgirl, also complete with hat, sitting in a classroom

writing the "lines": "I must not smoke cigars during prayers.

I must not smoke cigars during prayers . . . " (This was later reproduced

with the word "pot" replacing "cigars"![]() ;

many of the captions were subsequently changed or updated.)

;

many of the captions were subsequently changed or updated.)

ron9

However, violence continued to dominate the cartoons.

For example, one cartoon shows disconsolate girls being frisked as they

enter the school doors, with a growing pile of weapons on an incongruously

elegant and spindly table besides the (continuingly Victorian-looking)

mistresses: "Bang goes another pair of knuckledusters."![]() Another, untitled, shows the victorious hockey players raising their sticks

in triumph over the bodies of their opponents.

Another, untitled, shows the victorious hockey players raising their sticks

in triumph over the bodies of their opponents.![]() The mistresses are shown to be unbothered by all this, on one occasion

commenting simply "Cleaners getting slack, Horsefall" as they

step over the bodies littering the school corridor.

The mistresses are shown to be unbothered by all this, on one occasion

commenting simply "Cleaners getting slack, Horsefall" as they

step over the bodies littering the school corridor.![]()

ron10

Later the girls became actually demonic, with one cartoon

showing a girl writing the lines "I must be gooder" with her

devil's pointed tail doubling as a pen.![]() This also extends to the mistresses, with the girls lined up under the

banner "Welcome to our new Science mistress" as a witch flies

in over the gates.

This also extends to the mistresses, with the girls lined up under the

banner "Welcome to our new Science mistress" as a witch flies

in over the gates.![]() (Single women have often been accused of witchcraft.) However, girls continue

to commit arson and to drink: one cartoon shows a girl lifting a broken

bottle from her case with the caption "Hell! My best Scotch"

(Single women have often been accused of witchcraft.) However, girls continue

to commit arson and to drink: one cartoon shows a girl lifting a broken

bottle from her case with the caption "Hell! My best Scotch"![]() ;

and another, uncaptioned, shows simply a pair of legs emerging from a dustbin

surrounded by empty bottles, the inevitable boater resting on its lid

;

and another, uncaptioned, shows simply a pair of legs emerging from a dustbin

surrounded by empty bottles, the inevitable boater resting on its lid![]() .

As time progressed, though, these themes were tempered with others, slightly

more gentle, such as the parent being shown round the school's snooker

room: " . . . of course indoor games are an extra"

.

As time progressed, though, these themes were tempered with others, slightly

more gentle, such as the parent being shown round the school's snooker

room: " . . . of course indoor games are an extra"![]() ;

and the schoolgirl being comforted at the midnight feast: "Honestly,

darling, you don't look a day over nine"

;

and the schoolgirl being comforted at the midnight feast: "Honestly,

darling, you don't look a day over nine"![]() .

.

ron11

From the beginning, the cartoons received widespread public acclaim, as Webb has described.

The monthly appearance of one of "Searle's ghastly

schoolgirls" brought flooding into his bewildered hands enough press

cuttings to fill six large folio scrapbooks, and enough letters to fill

two volumes, and when the postman delivered one addressed simply to "Mr

Ronald Searle, St Trinian's, London", he began to feel that he was

sitting on a horse which had taken to the open country.![]()

Unsuprisingly, the cartoons soon appeared in book form, with the publication of Hurrah for St Trinian's! in 1947. Searle's biographer Russell Davies has noted that this:

expressed a sentiment with which he would never concur.

Even though scarcely more than a dozen St Trinian's drawings had yet appeared,

the invention of new horrors for the girls to wreak already looked likely

to become a chore.![]()

It is important to note here that Searle may have been

pleasing the British public, and, presumably, the children's book critics,

but he was not, as Marshall had been, happy to regard it as a key part

of his life's work. Hurrah for St Trinian's! was, however, followed

by The Female Approach (1949), which sold 16,000 copies; Back

to the Slaughterhouse (1951), of which the first print run of 20,000

copies sold out in six weeks; Souls in Torment (1953); The Female

Approach (New York, 1954); and Merry England etc (1956). Other

cartoons were included along with St Trinian's, but the books were marketed

on - and presumably sold because of - the St Trinian's content.

ron12

Hurrah for St Trinian's! was introduced by D.B.

Wyndham Lewis, who became "the girls' official chronicler"![]() when a writer was needed to accompany Searle's cartoons. He later published

a full-length novel with Searle, The Terror of St Trinian's (1952),

writing as Timothy Shy (45,000 copies of this were printed in the month

of publication), and also wrote the St Trinian's Soccer Song:

when a writer was needed to accompany Searle's cartoons. He later published

a full-length novel with Searle, The Terror of St Trinian's (1952),

writing as Timothy Shy (45,000 copies of this were printed in the month

of publication), and also wrote the St Trinian's Soccer Song:

Whack it up, girls! Bung the ball

Thro' Life's goalposts at the call.

Who can stay the Island Blood?

Rub their bustles in the mud!

Gallant hearts and bulldog pans,

Floreat St Trinian's!![]()

The reference to "Island Blood" makes it clear

that the girls are British girls. It suggests that the qualities which

"Island Blood" engenders in men become ridiculous in girls, who

do not as adults progress to the battle field. The fact that the girls

play soccer rather than hockey also suggests that their behaviour is unfeminine.

ron13

Wyndham Lewis was soon joined by

Arthur Marshall, previously the best-known parodist of girls' school stories

in the country![]() .

In "Look out King Wenceslas!", published in Lilliput in

1949, Marshall imitates the head of the school, "Madge", writing

to Maud, an old college friend, about the past term. When compared with

Alastair Sim's performance as Millicent/Amelia Fritton in the film comedies

which followed later

.

In "Look out King Wenceslas!", published in Lilliput in

1949, Marshall imitates the head of the school, "Madge", writing

to Maud, an old college friend, about the past term. When compared with

Alastair Sim's performance as Millicent/Amelia Fritton in the film comedies

which followed later![]() ,

it is clear that Marshall's characterisation was influential in shaping

both the character of the headmistress in the films and the actor's subsequent

performance of it.

,

it is clear that Marshall's characterisation was influential in shaping

both the character of the headmistress in the films and the actor's subsequent

performance of it.

. . . The American girl has made a great hit. I feared

that her name (Gloria Milton Zimmermann) might be against her, but when

she announced that she came from Chicago they were all over her. She has

been most generous, nylons for the Sixth (and yours truly!), refrigerated

steaks all round, and fearsome concoctions called Rye and Bourbon which

have caused much merriment in the studies. She showed them how to wire

a chair for electricity, and they put a sharp charge through Mademoiselle

just as she was getting into her stride with a La Fontaine fable. The current

was from the School plant, and obviously of no very damaging voltage, but

Mademoiselle made the most ridiculous fuss . . . Sometimes one really despairs

of foreigners . . .

Our new mistress, on the other hand, has been an absolute fiasco. Her name

was Miss Luker (they called her "Filthy" at once; how terribly

quick girls are!) and she simply never found her feet . . . I turned a

blind eye and quietly wrote off to Chitty and Gale for a replacement -

someone cheery who likes a joke, with Zoology, Geology, Calculus, Russian

and Chemistry.

November the Fifth was a merry affair, with bangs and explosions most of

the day and a monster bonfire (of desks! but I didn't get ratty) as soon

as dusk fell. One of the fireworks could not have been properly assembled

and blew all the Vicarage windows out: it was just like dear old 1940.

Our head girl, Rhoda Hornby (and a real fizzer), had a whip-round among

the Juniors and soon netted the cash. She laughingly called it Entertainment

Tax and everybody under fifteen had to stump up eighteen and sixpence.

There was some grumbling but she scotched that pretty pronto! It was a

fine example of leadership and initiative: Rhoda should make her mark at

Girton.![]()

ron14

Other writers also seized on the opportunity to bring

St Trinian's to life: Robert Graves wrote a "School Hymn for St Trinian's";

James Laver wrote The Fourth Form at St Trinian's; C. Day Lewis

wrote "A Short Dirge for St Trinian's (following the school's demise);

and Michael Flanders and Donald Swann wrote the song "Surly girls",

first performed in Penny Plain at the St Martin's Theatre, London in 1951.

ron15

Siriol Hugh-Jones suggests that the reasons for the cartoons' appeal are as follows:

First, let me timidly suggest, the deep English inverted

vanity that allows us to congratulate ourselves for finding funny what

we are supposed to hold most dear (in this case, the unsullied peaches-and-cream

English girl who is about to grow up, hurray! into the English mother).

Also the fact that, bar convents and M.I.5, English girls' schools are

the most closely guarded national mystery in existence, a conspiracy entered

into with verve by English womanhood in the shape of staff, mothers, and

non-communicative, enigmatic schoolgirls. Also, the fact that no one had

ever discovered this particular, and particularly lethal, joke before.![]()

(Of course Marshall had discovered a related joke earlier in the decade and must have influenced Searle to some extent.) Hugh-Jones believed that the cartoons appealed to men because:

most English men cherish a profound fear and distrust

of women of all shapes and sizes, particularly the shrewd, sharp canny

ones liable to grow up into astute turf accountants, or demon barristers,

or ace doctors specializing in forensic medicine.

This means that men can safely laugh themselves insensible at the Searle

girls, at the same time proving their point that females are basically

jungly and out to kill, and if you can't beat them you can at least lock

them away.![]()

This is a very astute analysis, and Hugh-Jones' reasons why women and girls enjoyed the cartoons are equally convincing, showing that there are a number of different ways to read the cartoons, and this is probably the main reason for their huge success.

women laugh because there were, and are, times when all

they long for is a small bomb or a sharp little cleaver, and because the

cartoons, for all the cheerful horror, are perhaps fundamentally on their

side. Confiscate a girl's gin, ban her tobacco, she will still find a way

to triumph over her environment . . .

St Trinian's is English womanhood - plain, imprisoned, disguised according

to Regulation Uniform Lists as trolls, demons, scarecrows, and under-privileged

gargoyles - against the world.![]()

Meanwhile girls enjoyed the cartoons because:

Searle composed, in line, the Schoolgirl's Marseillaise.

He took it calmly for granted that the Lower Fourth was in arms, and wistfully,

wishfully, in spirit they proudly rallied to the standard . . .

Searle made it all right to be plain, shapelss, and unhandy at dainty needlework.

You could still batter the world into submission with a blunt instrument.

Before Searle, the school heroine was the curly-haired Captain of Games

who looked clean through you with those straight, fearless grey eyes before

which a fib shrivelled and died of shame. Shame is a word unknown in St

Trinian's. For every girl whose uniform never fitted, whose hat looked

permanently on loan, whose mother worried silently and sighed audibly,

whose report commented on Absence of Team Spirit, whose arrival was marked

by a volley of sharp reports as elastic burst in all directions, whose

appearance suggested an abandoned Christmas parcel on which the temporary

staff at Mount Pleasant had worked off their grief and frustrations, Searle

came as a prophet of liberty and new self-respect.![]()

ron16

In later life, Searle himself wrote of the characters that:

The Staff, behind an extremely old-fashioned facade, conceal

equivalent excesses and plenty of lesbianism. They insist on good manners

at all times, and in all circumstances, but are extremely tolerant. Even

to the point of employing an abortionist-nurse to look after the school

creche, and care for the girls' babies while their mothers are busy in

the school lab, refining heroin base.![]()

It is interesting to note here that Searle draws attention

to the fact that the staff may appear to be "old-fashioned",

but that this conceals "lesbianism". This reflects the cultural

fears about women teachers and their influences![]() which had been the primary reason for the suppression of the genre of girls'

school stories.

which had been the primary reason for the suppression of the genre of girls'

school stories.![]() Searle continues of the girls that:

Searle continues of the girls that:

. . . [The girls' rooms] have been described as smelling

like a ladies' powder-room in Port Said . . .

[A St Trinian's girl] would be sadistic, cunning, dissolute, crooked, sordid,

lacking morals of any sort and capable of any excess. She would also be

well-spoken, even well-mannered and polite. Sardonic, witty and very amusing.

She would be good company. In short: typically human and, despite everything,

endearing.![]()

It is interesting to note that, by Searle's description,

it would be very difficult to identify a "St Trinian's girl".

A woman might appear to be well-spoken, even well-mannered, polite, sardonic,

witty, very amusing and good company, but in fact she could be sadistic,

cunning, dissolute, crooked, sordid, lacking morals of any sort and capable

of any excess. She might appear to be "straight and fearless",

but in fact she could not be trusted. This played heavily on cultural fears

about women, particularly the beliefs that women were incapable of being

"honourable".

ron17

"Endearing" or not, though, the cartoons were

a victim of their own success. By 1952 Searle decided that his life had

been dominated by them for too long and stopped drawing them, killing the

girls off in an atomic explosion the following year in Souls in Torment

(published by his own company, Perpetua Books). An additional reason for

Searle's action may have been a growing public concern about his cartoons'

influence on the young, fuelled by the tendency for the media to produce

stories such as "St Trinian's Girls Burned Their School" and

to blame Searle for the results.![]() To accompany the school's demise, C. Day Lewis wrote that:

To accompany the school's demise, C. Day Lewis wrote that:

It is my melancholy task, as the last surviving Governor

of St Trinian's, to announce the closure of this famous, nay, this unparalleled

school. Through circumstances which got out of control, it is no more .

. .

Those (and they are indeed the fittest!) who have survived the St Trinian's

experiment, will carry our Founder's gospel into other schools, where an

infusion of blood is sorely needed - and a little effusion of it can do

no harm. I am confident that our girls will soon settle down in their new

surroundings, and with the aid of those advanced techniques in the knuckleduster,

the knout, the hypodermic syringe, and the gin bottle which they learnt

at the dear old place, will rapidly assume positions of leadership and

responsibility. Though St Trinian's lies in ruins, the St Trinian's spirit

will arise from her ashes, like a vulture from the feast.![]()

And so it was to be. St Trinian's fame had long since

spread abroad, appearing in Tribune, Art News and France

Dimanche, and the girls had become unstoppable. Despite his intentions,

Searle's cartoons remained in print into the 1990s.

ron18

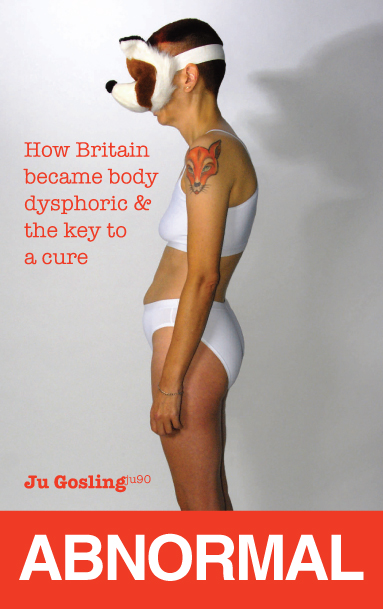

| Dr Ju Gosling aka ju90's ABNORMAL: How Britain became body dysphoric and the key to a cure is available now for just £3.09 for the Kindle or in a limited-edition hardback with full-colour art plates for £20 inc UK postage and packing. |  |