The

Brace/Borg

While

I'm proud to be disabled, being in this kind of

pain is not a lot of fun, so in November 1996 I obtained a referral to

the aptly named Henry V. Crock, Consultant Spinal Surgeon at the Cromwell

Hospital's Spinal Disorders Unit. He suggested that, since mobilising my

spine through exercise only tended to aggravate the pain, immobilising

it might allow the inflammation to calm down and perhaps even to heal permanently.

He therefore referred me to Kelvin Smith, an orthotist based at the Royal

National Orthopaedic Hospital, who made a plaster cast of my body in order

to mould me a custom-made spinal brace. As well as immobilising my spine,

the brace would encourage me to stand naturally, if crookedly; twenty years

of trying to force my body into having a "normal" silhouette - after being

accused repeatedly by doctors of having "bad" posture - had not helped

my pain.

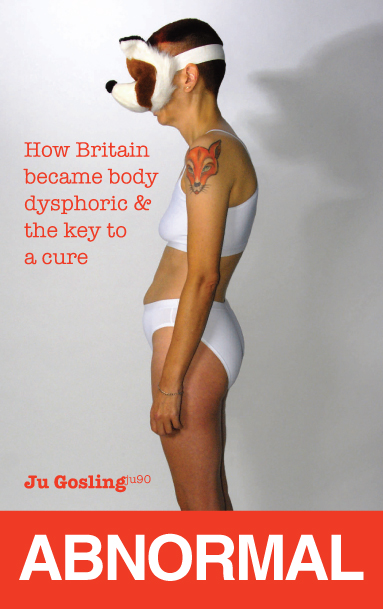

The

brace, which was made of plastic, covered the full length of my spine and

was fastened tightly with a number of nylon straps. While I was delighted

at the prospect of being in less pain, trying the brace on for the first

time was a frightening experience. The feeling of being confined made me

panic and hyperventilate, and the brace's appearance filled me with horror.

Its white nylon straps were made of the same material as the fastenings

on my racing dinghy. Its surgical pink surface took no account of ethnic

difference: if you were "white", you were pink. Its shape exaggerated my

waist and hips, while my breasts were the only part of my torso left exposed,

creating a feminised, almost Edwardian silhouette. And the hospital had

taken great care to ascertain my marital status, labelling it by my "lack"

of a husband as belonging to "Miss" Gosling (a title which I never used)

in a manner which suggested (rightly, but for the wrong reasons) that it

would always be that way.

At

this point I was only barely aware of the artist Frida

Kahlo and had never seen her famous self-portrait in her brace, so

I was unable to draw the inspiration from her which, thanks to the History

of Modern Art and Design research students at Falmouth - who made the connection

as soon as they met me - I later gained. Added to the fact that almost

none of my clothes would fit either under or over the brace, I felt my

identity dissolve; the brace had claimed me, borg-like, to wear it. I fitted

into the brace, but the brace did not fit me. My androgynous image had

vanished; instead the brace/borg exaggerated my femininity and impairment

whilst conflating the two.

This

increased my sense of confinement, a negative image of disability which

I had always fought against. Like a wheelchair, the brace was meant to

liberate me, by allowing me to do more than I could otherwise; like a wheelchair

(despite most people's misconceptions), I could leave it when I wanted.

But now my personality was trapped within the borg/brace. The only answer

was to reassert my ownership, to assimilate the brace within myself rather

than continuing to be assimilated by it.

Next:

From Borg to Cyborg

Return to My Not-So-Secret Life as a Cyborg

Return

to Ju Gosling's Home Page