From

Borg to Cyborg

One

reason why disability aids are commonly perceived as having negative connotations

is the depersonalising, identity-stripping effect of their stifling uniformity

and medicalised appearance - our aids reduce us to and categorise us by

our impairments in a reflection of the way in which the medical profession

treats us. I had already discovered the difference which a personalised

aid makes with public reactions to my much-admired stick, which was carved

by Rick Leech out of one piece of hazel, with the handle in the form of

a seal with buffalo horn eyes. My stick signifies something very different

to the standard metal, medical aid - its unique appearance restores its

associations with gender-bending, clowning and discipline, as well as,

in this case, having connotations of paganism and shamanism - but it performs

exactly the same task.

One

reason why disability aids are commonly perceived as having negative connotations

is the depersonalising, identity-stripping effect of their stifling uniformity

and medicalised appearance - our aids reduce us to and categorise us by

our impairments in a reflection of the way in which the medical profession

treats us. I had already discovered the difference which a personalised

aid makes with public reactions to my much-admired stick, which was carved

by Rick Leech out of one piece of hazel, with the handle in the form of

a seal with buffalo horn eyes. My stick signifies something very different

to the standard metal, medical aid - its unique appearance restores its

associations with gender-bending, clowning and discipline, as well as,

in this case, having connotations of paganism and shamanism - but it performs

exactly the same task.

Similarly,

when I was a child, and particularly when I was a teenager, I hated wearing

glasses because of the very limited and medicalised choice of styles available,

and because of the verbal and physical abuse that was associated with being

marked as visually impaired. Today, market forces have ensured that glasses

have become fashion accessories, due to the fact that, in the UK, glasses

are now manufactured by private companies rather than the National Health

Service. The development of contact lenses has also meant that visual impairments

can be disguised. The disabling effects of my visual impairments, therefore,

have now disappeared.

Unfortunately,

most disability aids are still produced or prescribed by the National Health

Service, and in many cases ownership still rests with the state rather

than with the disabled person who uses them. Private purchases are very

expensive and beyond the means of most disabled people, who have the lowest

average incomes in the country - myths of generous state benefit systems

and insurance policies notwithstanding. So most disabled people are unable

to "own" their aids in any sense, with the result that their aids are the

first thing which is noticed about them, and they are immediately classified

as disabled by the specatator. Yet when an aid is personalised, the person

using the aid is revealed beneath the social identity.

In

1996 I was therefore very fortunate to meet Jo Lang, a costume designer

who trained at Falmouth and Bournemouth Colleges of Art. Jo creates costumes

with attitude under her own label, Kiss My Ass, and luckily regarded transforming

the brace as a challenge. She took my vague ideas and realised them far

better than I could have imagined, whilst still allowing me ongoing input

and control. It is to her credit that a stallholder at Kensington Market

is one of several people who have since viewed the brace simply as clubwear

- even when told differently - and who have openly desired it, thus completely

reversing its stigma.

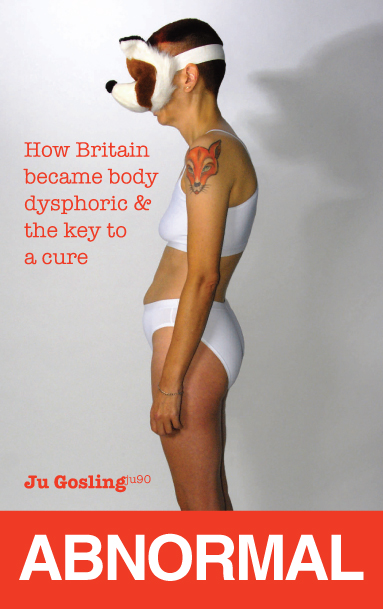

Our

over-riding aim was to make the brace more comfortable to wear, in every

sense. I had no wish to deny my impairment, to disavow my deviance. Making

impairment visible illuminates a fundamental truth: the perfect body does

not exist, and its illusion can only be maintained while the disabled body

is hidden from sight. At the same time, I did not want to be medicalised

by the appearance of the brace. Medical images are those of surveillance

and social regulation, used to classify, discipline and manage the body.

Meanwhile media images of disabled people distort us as objects of pity,

as a burden to others, or as super-crips who have overcome what is seen

as the tragedy of our lives, and these images are played up by charities

which are run by and largely employ non-disabled people in order to get

donations. I therefore wanted to control my own image, to mark my body

in a way which was meaningful to me, and to reject my body's classification

by its impairment.

There

are two environments where I feel most comfortable: the beach; and cyberspace.

I was conceived and grew up by the sea, and have always chosen to spend

my holidays there. Since becoming disabled, I feel more comfortable walking

on sand than on pavements, and the warmer the sunshine, the more my impairment

diminishes. And I can achieve more physically in the water than on the

land - even trapezing a racing dinghy and body boarding during my fittest

periods. As a pagan, the beach is also important to me as the shifting

border between land and the ocean. Paganism recognises the one true essentialism:

that we are an inseparable part of nature. Paganism has been very helpful

to me in coming to terms with impairment, since it reminds us that our

efforts to control nature are illusory; instead, nature controls us.

However,

I have always been charmed by technology and felt comfortable with it.

The Mac environment, where I moved in 1994, is one where I feel particularly

at home, especially since it allows me to customise the interface. While

my impairment still impedes my work, cyberspace itself is not an inherently

disabling environment (although

it can disable).

In addition, travelling in cyberspace literally allows me to detach myself

from my body, since the concentration involved diminishes my awareness

of pain. And hypermedia has provided me with a way of combining my

skills and interests where none previously existed, so in a real sense

I feel born to it as well as to the beach. We decided, then, to use both

beach and techno imagery within the customisation.

In

customising the brace, Jo and I also wanted to reflect and challenge attitudes

towards disabled bodies. Both of us are opposed to the false worship of

the unattainable perfect body, as reflected in the objectification of gay

men's and straight women's bodies and in debates about creating "post-humans"

and "leaving the meat". So we wanted the brace to present me as a proud

object of desire, rather than as medicalised and asexual.

(Disabled

people are commonly perceived as being asexual, and as sterile and/or lacking

the right to breed - around the world, many disabled girls are forcibly

sterilised or given injectable contraceptives such as Depo Provera; while

pregnant women are urged to have abortions, and when they do not, their

children are often taken away from them. When disabled people's sexuality

is recognised, it is regarded as being deviant, and as objects of desire

we are exoticised and fetishised. So in a very real sense, all disabled

sexuality is queer.)

I had

also been following the cyborg/body debate with interest over a number

of years, and discussed it in detail in My Experiences as a Disabled

Researcher, a hypertext which is included with my

PhD hyperthesis. I felt that the cyborg, an artificial human who is

partially inorganic, was a useful visual metaphor to use, both in terms

of popular culture and in terms of the academic cyborg debate which is

currently so popular in studies ranging from art to communication to the

body. I also wanted to locate myself as a disabled woman within those discourses,

because the disabled body is currently absent from them, whereas if it

were included, many of these discourses would be problematised.

For

example, the idea that, in the new millennium, we will all be augmented

and upgraded by technology would be undermined by the realisation that

scientists can't produce an artificial hip joint which will reliably last

longer than ten years, and indeed, that the body is so resistant to being

"upgraded" that people who have had transplants need to take drugs for

the rest of their lives to prevent rejection. Likewise, the idea that we

will all be able to take so-called "smart drugs" to enhance our abilities

would be problematised by including the experiences of disabled people,

given our awareness of the side-effects of drugs, and our knowledge that

the drugs we rely on may also shorten our lives or even kill us.

Cyborgs,

too, are seen on the one hand as being asexual, genderless, and on the

other hand as being extremely sexual - think of Fritz Lang's Metropolis,

or the Star Trek character Seven of Nine. This is echoed, not just in the

perception of disabled people as being either asexual or deviant lovers,

but also as genderless - to give an example, public toilets in the UK are

divided into those for Men, Women and the Disabled.

The

cyborg body, too, is a combination of technology and the organic, and disabled

people are commonly visualised as being partially inorganic when we use

technology to extend our abilities. For example, wheelchair users are described

as being "confined to a wheelchair", which gives the impression that they

remain in their chairs even whilst asleep. For some reason, disabled people's

use of aids such as sticks, braces and wheelchairs is regarded as being

fundamentally different in nature to the other ways in which we rely on

technology to live our daily lives in the West. The use of cars, bicycles,

phones, computers, domestic technology such as vacuum cleaners and washing

machines - all these, in contrast, are seen as being entirely natural.

Equally, the use of chemicals such as contraceptives to alter the body

is seen as being entirely different to the use of insulin or anti-depressants.

(Although it is also true that, for me, the use of my stick has become

natural - when I am tired and watching the television, I often find myself

wondering how a character is getting up and walking without the use of

one . . . )

Cyborgs,

too, are visualised as being less than human within popular culture, and

therefore as not being deserving of human rights. Indeed, cyborgs are often

seen as being a threat to humans, and therefore require containing. Disabled

people, meanwhile, lack human and civil rights throughout the world. We

are also seen as dangerous - in popular culture, physical impairment is

used as a metaphor for evil, while IRL, women with mental health needs

are stigmatised as potential killers and are forcibly drugged, restrained

and imprisoned.

As

a disabled woman, therefore - and as a queer, androgynous woman who has

frequently been mistaken for a gay man and who does not conform to a number

of female roles; who is white but of indeterminate ethnic background; from

a mobile class background; with an impairment that ranges between leaving

me bedridden to participating in watersports; with eyes that have been

augmented by glasses and later by contact lenses since the age of seven;

with a number of identities as a result; with a memory and brainpower which

has been augmented by a Psion palmtop computer since 1992; and with my

ability to communicate enhanced by a mobile phone since 1994 - I felt that

I could justifiably claim and explore a cyborg identity.

I also

like the cyberpunk ethic, having begun my career

as the editor of a zine with an explicit punk philosophy. And as I am hooked

on the usual techno-pagan mixture of popular culture, I greatly preferred

the idea of looking like an extra from Star Trek to one from Casualty.

Jo and I therefore decided to combine surf and cyberpunk imagery to transform

the brace, changing borg to cyborg, geek_girl to net_surf_chick and "Miss"

Gosling to ju90.

Next:

Kiss My Ass

Return to My Not-So-Secret Life as a Cyborg

Return

to Ju Gosling's Home Page

One

reason why disability aids are commonly perceived as having negative connotations

is the depersonalising, identity-stripping effect of their stifling uniformity

and medicalised appearance - our aids reduce us to and categorise us by

our impairments in a reflection of the way in which the medical profession

treats us. I had already discovered the difference which a personalised

aid makes with public reactions to my much-admired stick, which was carved

by Rick Leech out of one piece of hazel, with the handle in the form of

a seal with buffalo horn eyes. My stick signifies something very different

to the standard metal, medical aid - its unique appearance restores its

associations with gender-bending, clowning and discipline, as well as,

in this case, having connotations of paganism and shamanism - but it performs

exactly the same task.

One

reason why disability aids are commonly perceived as having negative connotations

is the depersonalising, identity-stripping effect of their stifling uniformity

and medicalised appearance - our aids reduce us to and categorise us by

our impairments in a reflection of the way in which the medical profession

treats us. I had already discovered the difference which a personalised

aid makes with public reactions to my much-admired stick, which was carved

by Rick Leech out of one piece of hazel, with the handle in the form of

a seal with buffalo horn eyes. My stick signifies something very different

to the standard metal, medical aid - its unique appearance restores its

associations with gender-bending, clowning and discipline, as well as,

in this case, having connotations of paganism and shamanism - but it performs

exactly the same task.