Why adorn equipment?

by Ju Gosling aka ju90

We

live in an age where we are surrounded by equipment and machinery that we rely

on to aid and extend our abilities, and thus to make life easier. Some of this

aids our most basic bodily functions, such as cooking and eating utensils, clothing,

seating and bedding. Some extends our domestic capabilities and conserves our

time, such as washing machines, dishwashers and hoovers. Some extends our mental

abilities, such as personal organisers and calculators. Some extends our ability

to communicate, such as mobile phones and pagers. Some extends our mobility,

such as bicycles and cars.

We

live in an age where we are surrounded by equipment and machinery that we rely

on to aid and extend our abilities, and thus to make life easier. Some of this

aids our most basic bodily functions, such as cooking and eating utensils, clothing,

seating and bedding. Some extends our domestic capabilities and conserves our

time, such as washing machines, dishwashers and hoovers. Some extends our mental

abilities, such as personal organisers and calculators. Some extends our ability

to communicate, such as mobile phones and pagers. Some extends our mobility,

such as bicycles and cars.

We take all of this equipment for granted, we think of it as

being "natural" - despite the fact that many people in the world are

without some or all of it, and that we can all survive without it. We also think

it is natural for this equipment to be designed well, and to be aesthetically

pleasing. And we think it is natural to have a choice of designs available to

us, because we all have different needs and tastes. For example, we think nothing

of the fact that we can buy a range of different covers for our mobile phones,

offering us a variety of colours and patterns to suit our different moods and

lifestyles.

Why, then, do we also think it is natural for any type of equipment

designed specifically to meet disabled people’s needs to be uniform, unadorned,

ugly, medicalised and unfashionable? Why do we take it for granted that disabled

people do not have the same range of tastes and desires as everybody else? Why

are those with the least uniform bodies treated as having the most uniform needs?

Perhaps one reason is that disabled people are often regarded

as being less than human - after all, we do not enjoy the same civil and human

rights - and therefore as not requiring the same consideration as other people.

But this is clearly ridiculous. The human "norm" is in fact non-existent.

Everybody is a unique mixture of strengths and weaknesses - emotional, physical

and intellectual - and these vary over time. Throughout history, it has been

as normal to be disabled as to be non-disabled: archaeologists continue to excavate

skeletons of warriors, chieftains and ordinary people who also happened to be

disabled.

Perhaps another reason is the impact of more recent history.

With the dawn of the Industrial Revolution and mass production, equipment and

manufacturing was standardised to meet the needs of the "standard"

body, and people with "non-standard" bodies were excluded. Working-class

disabled people, who previously had always had a role to play in society, were

now regarded as useless if they could not access and operate standardised machinery

- despite the fact that many of them became disabled as a direct result of this

work. Meanwhile middle and upper-class disabled people were treated as "invalids",

a highly romanticised and desirable group, and could access equipment that was

tailor-made to meet their needs.

Then, in the 20th century, the introduction of the National Health

Service alongside state socialism set a norm of standardisation. The needs of

the "non" - or "sub-normal" body were categorised alongside

that of the "normal", so the response to those needs could also be

standardised. Doctors, too, categorised both impairments and disability aids

in a desire to understand the world through a "scientific" system

of classification, rather than accepting that everyone’s experiences of

impairment and the needs resulting from these are different. Meanwhile the 19th-century

producers of bespoke equipment for disabled people largely disappeared.

Perhaps another reason is punishment. Disabled people embody

truths that we find unpalatable in today’s society: we are all mortal;

and science’s ability to "cure" - to triumph over nature - is

very limited. It is easier to blame disabled people for failing to get "better",

or for sinning in the eyes of our gods. Certainly we use the language of punishment

when describing disabled people’s relationship to their equipment: we talk

about being "confined" to a wheelchair, or "forced" to use

a walking stick or spinal brace. Yet, as with mobile phones and bicycles, this

equipment is extending our abilities, and thus is liberating rather than confining.

As a society, we also subscribe to the myth of the "perfect

body", and perhaps we desire to punish or dismiss disabled people for so

obviously not having this. But our ideas of "perfection" are flawed:

we are all imperfect; or, to put it another way, we are all perfect. Acknowledging

this fact rather than continuing to aim for the impossible would make the 21st

century a happier place to live for all of us.

Certainly one reason is economic. Disabled people are the poorest

group within society, and have the highest daily living expenses. This means

that the majority of us rely on the state to provide us with specialist clothing

and equipment, either through the NHS or social services departments, with ownership

generally remaining with the state. This means that, while meeting the needs

of disabled people is a massive industry, disabled people themselves do not

have any consumer power. Meanwhile the state continues to accept the status

quo of poor design as being "natural".

Yet when we adorn our equipment, when it reflects our individuality

and our personality, when its design meets the same high standards as equipment

for non-disabled people, we ourselves are revealed. Not as abnormal, defective,

deformed, in-valid, incapable, genderless, asexual or deviant, but as people

with the same range of needs and desires as everyone else. Only when this is

done will others see the things that really disable us - the abuse, discrimination,

prejudice and poverty, the rejection, isolation and institutionalisation, the

excluding design of our environment - and realise that it is this, not our bodies,

which needs to change.

Why adorn equipment? The real question is: why not?

Ju Gosling aka ju90 is a

writer and multimedia artist.

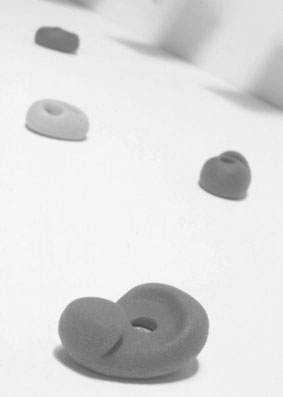

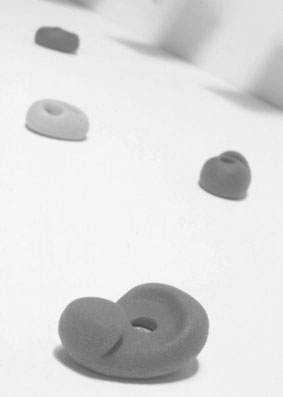

Illustration: Handy Grips by Kelly Sant

© The City Gallery,

Leicester and the artists: 2001

This site was built by Ju

Gosling aka ju90 during an artist's residency at Oriel

31 in November 2001

Return to top of page

We

live in an age where we are surrounded by equipment and machinery that we rely

on to aid and extend our abilities, and thus to make life easier. Some of this

aids our most basic bodily functions, such as cooking and eating utensils, clothing,

seating and bedding. Some extends our domestic capabilities and conserves our

time, such as washing machines, dishwashers and hoovers. Some extends our mental

abilities, such as personal organisers and calculators. Some extends our ability

to communicate, such as mobile phones and pagers. Some extends our mobility,

such as bicycles and cars.

We

live in an age where we are surrounded by equipment and machinery that we rely

on to aid and extend our abilities, and thus to make life easier. Some of this

aids our most basic bodily functions, such as cooking and eating utensils, clothing,

seating and bedding. Some extends our domestic capabilities and conserves our

time, such as washing machines, dishwashers and hoovers. Some extends our mental

abilities, such as personal organisers and calculators. Some extends our ability

to communicate, such as mobile phones and pagers. Some extends our mobility,

such as bicycles and cars.