Image, ability by

Julia Cassim

Fashion

and lifestyle magazines are a genre not known for their longevity. There are

of course exceptions, the September 1998 issue of 'Dazed

and Confused' being one of them. Mention its contents and even trend-hungry

fashion victims for whom last week was ancient history remember it in the way

that others recall their precise whereabouts on the day that John F. Kennedy

or Jill Dando were shot.

Fashion

and lifestyle magazines are a genre not known for their longevity. There are

of course exceptions, the September 1998 issue of 'Dazed

and Confused' being one of them. Mention its contents and even trend-hungry

fashion victims for whom last week was ancient history remember it in the way

that others recall their precise whereabouts on the day that John F. Kennedy

or Jill Dando were shot.

Guest-edited by 'bad-boy' designer Alexander McQueen, the magazine

featured a series of photographs by Nick Knight. They showed young disabled

people modelling clothes created for them by McQueen and his contemporaries

- Hussein Chalayan, Philip Treacy, Roland Mouret, and Catherine Blade. David

Toole of the CanDoCo Dance Company was

seen balanced on one hand, the unfurled fan of his ivory costume shooting upwards,

mirroring the movement of his body. Aimee Mullens striking a domineering pose

in a crinoline corset looked contemptuously down at the lens, balanced on two

muddied prostheses like a pastoral Marie-Antoinette. More daringly, Chalayan

made the naked body of Alison Lapper his canvas, using colour and light to create

a minimalist patchwork that emphasised her statuesque, limbless form.

To say that the images were sensational is to understate the

case for they marked a profound sea change in attitude. That they appeared in

a magazine devoted to ephemera and not social issues brought under scrutiny

the print media's portrayal of disabled people as well as who controls what

is seen. In this narcissistic age, Gerri Halliwell or Posh Spice's stripped

down or surgically enhanced bodies are presented as emblems of moral worth -

the essence of their personhood, branded images splashed across the pages of

tabloid and broadsheet alike. Readers may snigger at the pair's vanity and presumption

but unquestioningly adopt them as role models for their own body beautiful -

'One can never be too thin or too rich' quoth the Duchess of Windsor in the

1930's and the message has not changed one whit to this day.

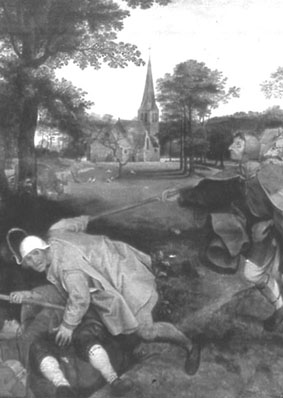

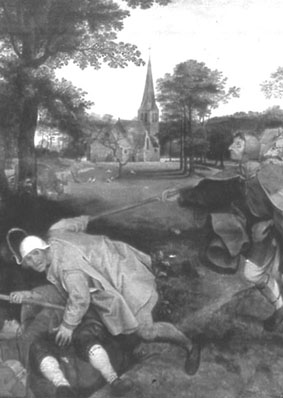

For disabled people the record got stuck long ago - five centuries

separate Pieter Bruegel the Elder's 'Parable of the Blind Men' of 1568 and Diane

Arbus' 1960's images of dwarfs, Jewish giants and adults with ‘Downs Syndrome’.

In attitudinal terms, little separates the two. Yet the latter's images are

accepted unquestioningly as a valid aesthetic by heavyweight critics like Susan

Sontag who in turn influence art historians, curators and so on down the visual

arts food chain. It is part of the 'enfreakment' of photography as described

by David Hevey which only becomes a hotly debated issue in the public domain

when 'heroin chic' or images of underage anorexia become the dominant fashion

aesthetic and a threat to public health. Show the images of Arbus and they are

read as objective social commentary, nothing more.

Awareness of the issues of representation of minorities has unquestionably

risen and times are now more politically correct. Yet unlike other communities,

disabled people continue to be caught in a particular bind and it is not one

of their own making. Aside from the 'tragic but brave' or 'battling the odds'

news stories of disabled achievers, any striking image of a disabled person

we see is likely to be part of a poster campaign for a major charity. The aim

is to raise awareness of the issues affecting the depicted community but the

effect can be quite different. For there's nothing like fear and pity to induce

people to give generously, the underlying reason for this dual exercise in consciousness

and fundraising. Inevitably, images and text tend to reflect this uneasy marriage.

How many of these posters show disabled people as masters of their own fate

and not the passive 'victims' of their condition, singled out and set apart?

Like it or not, body image rules OK! Yet the message seems lost

on the designers and manufacturers of the aids and equipment used by an estimated

four million of the 8.4 million disabled people in the UK who come under the

aegis of the Disability Discrimination Act.

Many of their products are functional, innovative in their use of technology

and may meet the specific clinical needs of their users, yet fail miserably

to address their aesthetic or lifestyle aspirations. Engineered rather than

designed, these essential aids stigmatise rather than integrate. Unwittingly,

they reinforce images of disability not ability and present the medical and

not social model of disability for our view. The inventions of Heath Robinson

may conjure affectionate smiles on the faces of the non-disabled people but

imagine the situation, where the equipment and aids so crucial to one's daily

independence and quality of life bear his aesthetic stamp.

This awareness of the key role played by design lies at the heart

of the work of the Helen Hamlyn Research

Centre - a centre for inclusive design at the Royal College of Art. Working

with students and a range of external partners, our programmes aim to show how

design can empower, promote quality of life and be a force for social inclusion.

Each year postgraduate design students consult with user groups drawn from communities

traditionally marginalised or excluded wholesale from the design process - older

people, young disabled people and those affected by rapid social change. The

raw data from these sessions is transformed into innovative prototypes for products

and services in four themed categories - work, age, mobility, and care. These

are shown as part of the students' final degree show in a competition called

'design for our future selves' which draws increasing of entries each year.

This year, Guy Robinson's 'Life Supports'

took the first prize in the care category with his radical ergonomic and aesthetic

redesign of crutches. By relocating this standard item in sports and not medical

culture, he shifted the design model. With equal emphasis placed on body image

and functionality, Robinson recognised that an aid is more than a piece of equipment

to the disabled user. It is an extension of the body as crucial to it’s

users self image as a tattoo, designer frock, toned body or whatever else he/she

wishes to convey. Three years ago, 'Dazed and Confused' threw down an unequivocal

gauntlet to the fashion industry whose effects continue to be felt. Two decades

after the International Year of Disabled People of 1981, it is certain that

this exhibition will achieve the same long-term effects in the self-contained

world of museums and beyond.

Julia Cassim is editor of 'innovate' the research and development

journal for small firms in the care and disability sector, and is research co-ordinator

of the Small Business Programme at the Helen

Hamlyn Research Centre, Royal College of Art

Illustration: 'Parable of the Blind Men' 1568 (detail) Pieter

Bruegel the Elder

© The City Gallery,

Leicester and the artists: 2001

This site was built by Ju

Gosling aka ju90 during an artist's residency at Oriel

31 in November 2001

Return to top of page

Fashion

and lifestyle magazines are a genre not known for their longevity. There are

of course exceptions, the September 1998 issue of 'Dazed

and Confused' being one of them. Mention its contents and even trend-hungry

fashion victims for whom last week was ancient history remember it in the way

that others recall their precise whereabouts on the day that John F. Kennedy

or Jill Dando were shot.

Fashion

and lifestyle magazines are a genre not known for their longevity. There are

of course exceptions, the September 1998 issue of 'Dazed

and Confused' being one of them. Mention its contents and even trend-hungry

fashion victims for whom last week was ancient history remember it in the way

that others recall their precise whereabouts on the day that John F. Kennedy

or Jill Dando were shot.