Talkabout adorn, equip

Ju Gosling aka ju90

I'm

going to divide this talk into three parts. First, I'm going to talk about my

own experiences of disability aids and equipment over the past few weeks, in

order to give you some insight into the relationships which disabled people

have with their aids and equipment and with the people who provide them. Then

I'm going to talk to you about my video installation which is being shown in

this exhibition, 'Fight', and about how it was developed and what its meaning

is to me. Then I'm going to open it up to discussion, where you can ask questions

and make your own points about the exhibition and its themes.

I'm

going to divide this talk into three parts. First, I'm going to talk about my

own experiences of disability aids and equipment over the past few weeks, in

order to give you some insight into the relationships which disabled people

have with their aids and equipment and with the people who provide them. Then

I'm going to talk to you about my video installation which is being shown in

this exhibition, 'Fight', and about how it was developed and what its meaning

is to me. Then I'm going to open it up to discussion, where you can ask questions

and make your own points about the exhibition and its themes.

In my essay for the catalogue, 'Why

adorn equipment?', I've discussed some of the possible reasons

why disability aids and equipment are currently so uniform, ugly and badly designed,

so I won't repeat that here. What I am going to talk about is the impact

that this has on us as disabled people, using my own personal experiences.

I've been seriously ill over the last 18 months, and that

has left me needing additional support in terms of equipment to live life to

the full. As well as this, I've had ongoing needs because of my impairment,

so I've been experiencing the full horror of dealing with the NHS, social

services and equipment suppliers. And it has been horrible, whereas it should

have been so very different.

Ultimately, there is no reason why disabled people should not

have positive, uncomplicated relationships with the equipment that we use because

of our impairments. We have positive, uncomplicated relationships with other

equipment such as mobile phones or hoovers that improve our quality of life,

so why should disability aids and equipment be any different? If items were

well-designed, looked good and met our needs as individuals, and if equipment

suppliers and providers treated us in the same way that customers of other service

industries are treated, there would be no problem.

Sadly, though, the reality is very different. It's been

hard to know quite where to start in talking about my recent experiences, even

though my own title for this section of the talk is DGMS, which is shorthand

amongst my friends for Don't Get Me Started . . . So anyway, I'll

start with wheelchairs, since these are always used as a symbol for disabled

people - despite the fact that, of course, 95 per cent of disabled people

don't actually use them.

I have two wheelchairs, a manual chair and a powered chair. The

manual chair is provided by the NHS and the powered chair by the Government's

Access to Work scheme, and they continue to belong to them. And that, I think,

illustrates the first difference between disability aids and equipment and other

domestic equipment: disabled people rarely have any ownership; and so have no

consumer power.

A manual chair is ideal when I am, for example, attending a gallery

opening. Then I need a comfortable, easily moveable seat to avoid standing for

long periods, or alternatively sitting in pain on an uncomfortable chair, unable

to get around to join in conversations. My spinal condition means that I can't

propel myself for long distances, but I can manage short ones, while unlike

a powered chair, a manual chair is also, theoretically, light and easily folded

away to transport.

What makes my chair unsuitable for me is its weight, which means

that I can't fold it up or put it into a car independently. And this in

turn means that I can't be independent when I'm using it. It's

a classic illustration of how I am not disabled by my impairment, nor even,

when a gallery is as accessible as this one, by my environment, but by the very

equipment that is supposed to liberate me. And in this case it is not because

lightweight chairs don't exist - they do, in abundance - but

because the NHS will not provide them, and the costs are so high that I cannot

afford them.

The fact that the NHS owns my chair creates other problems, too.

I can't do anything to adorn my chair or to personalise it, because I would

be in breach of the conditions under which it is provided. If I did this, I

would risk losing the chair completely, and with it some of my mobility. And

because the NHS owns the chair, the contractors who provide it for them do not

treat me with any of the respect with which private clients would be treated.

To give an example, a few weeks ago there was a loud thundering

on my front door at 8.30 in the morning. My postman knows that it takes me a

long time to get up in the morning, and if he has a package for me, he waits

and then, if I don't appear, knows that I'm feeling too unwell to answer the

door. Meter readers and so on will usually go away if the door is not answered.

And as the after-effects of my illness mean that I can collapse easily in stressful

situations, I never see anyone without an appointment.

But the person at my door was so insistent that I thought it

was an emergency, and went down two flights of stairs to answer the door despite

it not really being safe for me to do so. I unbolted the door, put the chain

on and opened it, still only wearing my dressing gown. And thus I discovered

that it was someone from the wheelchair contractors, come to service the chair

without any notice whatsoever.

And despite the fact that I obviously wasn't even dressed, he

tried to insist on coming in; only the chain stopped him from forcing himself

past me. As a disabled person, I was invisible, irrelevant, undeserving of any

consideration. As you can imagine, I found this very upsetting and stressful,

and this in turn had an impact on my overall health and wellbeing. Would this

happen in any other sector of the service industry?

Likewise, when I was booked to do this residency at Oriel 31,

I knew that I would need a new set of batteries for my powered chair, because

they tend to need replacing every year. And because the chair is supplied through

the Access to Work scheme, I needed to obtain a written quote first from the

company who originally provided the chair. It took me four weeks and numerous

phone calls before the promised quote arrived, but then I was assured - in writing

- that the batteries were in stock and could be fitted as soon as the quote

had been approved by the Department for Employment.

However, when I phoned up the week before I came to Wales to

arrange the delivery and fitting, the company said that they could not honour

their arrangement after all. The batteries were not in stock, and they had no

personnel free. They said that I would have to cancel my work here, and that

I should have contacted them for a quote more than six weeks in advance of when

I needed the batteries.

It was only when I threatened to publish the company's name on

my website that the batteries were delivered and fitted the next day. Again,

would this happen in any other sector of the service industry? Can you imagine

a garage, or a bicycle repair shop, that would stay in business for more than

a week with that attitude?

Anyway, because I do have a problem using stairs, I'm in

the process of applying for a grant from my local council to install a lift.

And this is my second example. My NHS occupational therapist arranged for a

lift company representative to visit me, in order to decide whether my house

was suitable for a stair lift or whether a through-floor lift would have to

be fitted. I would then be able to apply for a grant for the cheapest option

- my own preference was irrelevant, as was my wish to make my house accessible

to all of my friends, not just those who can use the stairs or a stair lift.

Well, anyway, the chap from the lift company decided that the

house wasn't suitable for a stair lift, literally sneering that he had

never seen such small stairs. So he decided that, rather than coming back to

carry out a survey for a through-floor lift, he would save his time by doing

it there and then. When I said that this wasn't convenient, he ignored

me - in fact he rarely spoke to me throughout his visit, addressing all

of his comments about the lift to the occupational therapist.

In fact, I was intending to spend that afternoon in my studio

with a sound engineer, completing the sound track for 'Fight', and

she was unavailable to finish it the following day. So as we struggled to overcome

various technical problems, the lift company representative moved around us

with a metal tape measure, at one point dropping it on to the computer without

even apologising.

I felt completely powerless to stop him. I was the home owner,

I was the client, I was the person who would be using the lift, but as a disabled

person, I was invisible to him. The disruption and stress that he caused meant

that we never did finish the soundtrack, so I had to take it over to a sound

studio and pay to have the work completed the following weekend.

And when the estimate was completed, I only found out from the

occupational therapist - the company did not even send me a copy of their

quote. So what should have been a really positive experience - originally

I was very excited about the increased mobility that I would have when a lift

is installed - was incredibly negative and upsetting.

I could go on and on about this kind of experience - I did

warn you that my own title for this part of the talk was Don't Get Me Started

. . . , but I decided that I'd confine my descriptions to the weeks leading

up to the opening of this exhibition and what has happened to me since. So,

my final example is my attempt to find a new bath.

As with the lift, I need to apply for a grant for this, not really

because a new bath should be beyond my means, but because an accessible bath,

as with all disability equipment, is incredibly expensive. And, as is so often

the case, accessible design, which benefits everyone, is the exception rather

than the rule. So, I took myself to the Independent Living Show at Wembley,

which is the annual London showcase for accessible equipment, and looked at

the best of the bath designs available.

My spinal condition means that the ideal way of bathing for me,

as with most non-disabled people, is to be able to lie down in the bath. However,

I wanted to find a bath which I could get into more easily than clambering over

the side, so I wanted one with a door. As with most disabled people, the effects

of my impairment vary, so I wanted a bath with a built-in lift seat, so that

I can have a proper bath even when I'm in a lot of pain. And I wanted to

be able to sit down and have a shower when I couldn't even do this.

At the show I found a great bath which does all of these things,

and looks good as well. It will cost over £5,000 to fit, which I think

is excessive, but as I've said, accessible equipment is very expensive.

An accessible bath like this one would in fact benefit most people at some point

in their life time, including parents of young children who often hurt their

backs lifting kids in and out of baths, but of course we do not, as yet, live

in an accessible world.

The problem, as I discovered when I'd thought about it more

and talked it over with a friend and my assistant, is that the bath wasn't

really accessible at all. Or at least, it was accessible with help, but not

independently, whereas it was being marketed at Wembley as an aid to independent

living. The reason was very simple: the bath taps were at one end of the bath,

whereas the seat was at the other. So if you needed to use it because you needed

to remain seated throughout, you couldn't switch the taps on or off by

yourself.

This illustrates a very common problem with so-called aids to

independent living. The vast majority of it was originally designed to be used

in residential care homes, and has been repackaged without being redesigned.

And, of course, disabled people haven't been consulted at any stage during

the design process.

It was unthinkable to Mark Prest, as curator of Adorn Equip,

that disabled people would be anything other than fully involved in the designs

for this exhibition. But it is equally unthinkable for most manufacturers of

disability equipment to consult us at all. And the bath salesman who later called

on me - who, fortunately, was as unlike the lift salesman as it was possible

to be - said that his wide-ranging experience was never drawn on either.

The fact that designers and manufacturers still believe, really,

that all disabled people belong in residential care homes was underlined by

some literature that the bath manufacturers sent to me. Although I completed

my PhD four years

ago, I've only recently had the means to pay my outstanding fees, and so

gained the right to call myself 'doctor'. And to even up the power

relationship a little and to ease my frustration, I've started insisting

that people like the bath salesman use it!

I was therefore not altogether surprised when I received a new

brochure for the same bath, this time not aimed at disabled people but at care

home owners. In their vision of the world, as a disabled person I cannot be

a doctor, in the same way that, as a doctor, I cannot be a disabled person.

The brochure which the salesman gave me as Ms Gosling, quote,

'illustrates how we can help you to regain bathing independence in your

own home'. It also assures me that 'with a lightweight removable seat,

no one will ever know you need assistance in bathing again'. Because being

disabled is, of course, something to be ashamed of . . . but don't get

me started!

Anyway, in contrast, the brochure which the manufacturers sent

me as Dr Gosling says: 'Being active in the provision of care, you will

be aware of the very diverse requirements that people in care have.' The

same bath in this context is, quote, 'designed to ease the lives of everyone,

carers and the cared for'.

Well, I like to be cared for, and I'm fortunate in having

in my life a lot of people who do care for me. But I don't want to be an

object of care - I'm neither a child nor a very old person. What I

want in my life is adequate help and support when I need it, and the means to

do without that help and support wherever possible.

Fortunately, in this case, the bath salesman was able to come

up with a solution, moving the bath out from the wall and the pipes to the middle

of the bath. But what was the designer thinking of?! Thank goodness for the

work of the Helen Hamlyn Research Centre,

which is training new designers to think about these issues, and whose students'

work is on show here today.

As you can imagine, I could go on and on, as I'm sure could

every one of the other disabled people here today. But I'm going to leave

that there now, and move on to talk about my installation, 'Fight'.

Although I'm now known for my writing and

multimedia work, my first art form was dance, and until I was sixteen I trained

to be a dancer. I stopped when my spinal condition developed, and its effects

meant that I was unable to continue with ballet training. At this time I felt

an overwhelming sense of artistic failure, and so turned my back on dance and

music for nearly twenty years.

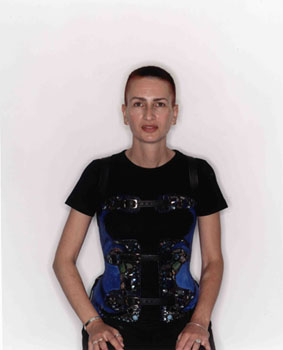

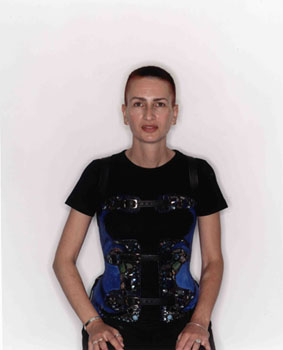

What brought me back to dance was being fitted for my first spinal

brace, at the end of 1996. I'd spent the intervening period covering up

my body with very baggy clothing, but when I got the brace, I found that these

clothes still weren't baggy enough to fit over it. When I went to buy new

clothing, I therefore had the choice of disguising my body shape still more,

or of buying tight-fitting clothing and revealing both my body and the brace.

I'm still not sure where I found the nerve to do it, but

it didn't take me long to decide to buy tight clothing, decorate the brace,

and to use the opportunity provided by wearing the brace to 'do disability'

as performance art. In other words, typical artist behaviour! Later I recorded

my experiences on my website, in a piece called 'My

Not-So-Secret Life as a Cyborg'. And much to my surprise, this work

has subsequently received international recognition.

One effect of this work was to make me think again about how

much dancing had formed who I am, and the extent to which I was still a dancer

- even though I didn't dance. And at the same time I came into contact

with a disabled dancer and choreographer, Petra Kuppers, who introduced me to

disability dance as an art form.

This in turn made me want to start working on a piece where I

would explore the disabled body and movement. In 'My

Not-So-Secret Life as a Cyborg', what I am writing about is my experiences

as I move about and interact with other people. But the self-portraits which

I produced to illustrate it are static, as are the portraits which other people

have produced of me wearing the brace.

I decided that I wanted to produce a very stylised, symbolic

movement piece, rather than trying to produce a documentary about my interacting

with non-disabled people in reality. I also decided that I wanted to produce

it as a film-dance piece, since I could never be sure of being well enough to

produce a live performance, and therefore I choreographed it for the camera

rather than for a live audience.

At the same time, I also wanted to explore what we mean by the

disabled body. Everybody is a unique mixture of strengths and weaknesses -

physical, mental and emotional - and these vary over time, so in many ways

the concept of a disabled body is a nonsense. I therefore decided to work with

a so-called non-disabled dancer on the piece.

The first stage of the work took place in July 1999, with the

support of a London-based organisation called Arts Admin. I spent a day working

on improvised movement with a performance artist called Helen Paris, directed

by Petra Kuppers.

This was the first time that I had presented myself as a dancer

since the 1970s, and I found it an emotionally challenging experience. I realised

that I had never dealt with my feelings about giving up dancing, and I had to

do a lot of work around that before I could move forward with the piece. Fortunately,

in October 1999 I ended up working on a series of portraits around memories

of dance with the photographer Ashley, and this was very cathartic. You can

see a triptych of these portraits on my website, entitled 'Dancing

with Darkness'.

Then, last year, I received a grant from London Arts' Combined

Arts Development Fund to research and develop the work further. As well as working

on the movement, this allowed me to buy sound and music equipment, and to begin

to develop the sound track of 'Fight'.

As I said, I'd given up music when I gave up dancing, and

more recently, when I had wanted to go back to making music, I'd been unable

to return to my original instruments because of my spinal impairment. So the

grant allowed me to buy a mini-disc recorder, keyboard and software, and I began

composition and sound engineering workshops at the Drake

Music Project, which trains disabled people to use music technology.

I've been interested for a long time in working with ambient

sound, and I decided that I would record a selection of sounds over a 24-hour

period as a starting point for the sounds in the piece. I decided that I'd

do this at the same time as I was undergoing a 24-hour ECG test to determine

the effects of my illness on my heart. I recorded the sounds of the traffic

as I journeyed to and from the hospital, the voices in the corridors and so

on, and I later obtained the soundwave patterns from the ECG itself for inclusion

in the work.

Helen Paris is normally based in the States, so in terms of the

movement, I began working with a dancer and movement analyst called Layla Smith,

who is also a personal friend. Layla and I spent about a week working together

in all, and this culminated in another day's improvisation directed by

Petra Kuppers, which we recorded on video.

In many ways this was a very poignant time in my life to work

on a piece which explored the disabled body and movement. I'd been so seriously

ill over the spring and summer of 2000 that I had never been less mobile in

my life, and I found this deeply ironic.

I couldn't see or hear properly, which meant that I lost

my balance very easily. I had neurological problems, which meant that I became

very easily confused. And generally very poor health, together with the effects

of this on my spinal impairment, meant that I had difficulty in even getting

from the front door to a taxi to attend regular hospital appointments.

In fact, the after-effects of my illness on my mobility mean

that I still haven't been out independently, even to the shops or to socialise.

So, like I said, it was a poignant and challenging time for me to produce this

piece. But, as an artist, of course, it was also perfect timing.

Anyway, once the research and development stage was completed,

I began to talk to Mark Prest, the curator of Adorn Equip, about completing

the work for inclusion in the exhibition. 'My

Not-So-Secret Life as a Cyborg' had been included in the Adorn Equip

work-in-progress exhibition in 1999, and Mark had been keen for a long time

to commission a new brace for me for the main exhibition.

If this could be done, the brace could then be incorporated into

my film-dance piece, since I am unable to do any movement work without wearing

a brace. The problem, though, lay in finding a brace maker - an 'orthotist'

- who wanted to be involved, since the brace would first have to be tailor-made

for me by an expert. And the medical profession in general have been very wary

of this exhibition . . .

Then, in late March of this year, I was contacted by Jonathan

Wright, an orthotist who's already had a very distinguished career, and

who was awarded the MBE for his work in war zones. Jonathan wanted to talk to

me about 'My Not-So-Secret

Life as a Cyborg', but I'm afraid that by the time I emailed him

back, I already knew what I wanted to talk about! And fortunately he agreed

to make a new brace for me for Adorn Equip.

This meant that Mark was able to ask Andrew Logan if he would

be interested in working with me to decorate the brace. Andrew is of course

known around the world for his mirrored mosaic sculptures and jewellery, and

I felt that his work would fit perfectly with my own.

Within 'My

Not-So-Secret Life as a Cyborg', I write a lot about the 'look'

to which the disabled body is constantly being subjected. I also write about

the way in which I try to play with that look, so that what the onlooker sees

is not what they expect, and they have to look again.

Equally, the self-portraits which illustrate the 'Cyborg'

website were shot with me standing between two mirrors. This was partly to illustrate

the distorted images of disabled people with which we are surrounded in the

media, and partly to illustrate the lack of non-distorted images, leaving us

with nothing but our own reflections.

Incorporating mirrors into my brace meant that the brace itself

would illustrate both aspects of my 'doing disability as performance art'

work: the 'look'; and reflections/distortions. Andrew and Jonathan

then worked with me to produce the really gorgeous brace which you see here

today, and it's a tribute to both of them and their professionalism that

they managed to do it in the short time I allowed them in order to give me time

to produce my own piece.

'Fight' was eventually shot in August, with the support

of London Disability Arts Forum.

Because the budget was very limited, it had to be shot in one day rather than

the two or more that was needed, and I was also unable to afford to produce

it to broadcast-quality standard, so technically it's not quite at the

standard which I would have liked. However, as is so often with these things,

I think the restrictions that the budget placed on the production also gave

it an edge that it wouldn't otherwise have had. In particular, the pressure

that Layla and I were under to complete the piece before we were thrown out

of the theatre meant that the tension in the piece was real rather than acted!

So, what is 'Fight' about? I say in my artist's

statement that it's also a self-portrait, and, as I've already talked

about a lot of personal issues here today, I'll take that as my starting

point.

From my birth to my early 30s, I was moving between a disabled

and non-disabled identity, partly because of my 'poor' health, partly

because of my body, which first became 'wrong' for dancing and then

developed a 'bad' back, and partly because of my 'poor'

eyesight. My disabled identity was not conscious, though, and so I had no Pride:

however I was identifying, I was very shy, very tentative, and very lacking

in self-confidence.

The first part of 'Fight' is intended to illustrate

this, with Layla representing my non-disabled identity and me representing my

disabled identity in my early years. We take it in turns to lead the movement,

and while the other has no choice but to follow, we avoid looking at or acknowledging

each other.

The repetitive C and G of the piano represents a ticking clock,

illustrating time passing, both in the first part of my life and during the

day when I had the ECG test, when I was acutely aware of time. The crashing

chords and slowed down movement represent the changes of dominance between a

disabled and non-disabled identity, and the lack of control over the body and

therefore of this process.

The reflections of Layla and myself in the mirrors represent

the lack of images of ourselves which we found as children and young adults,

while the children's voices represent the bullying which we were subjected

to for being mixed-race and queer. The traffic noise also represents time passing

and the journey through life.

Both the images and the sound reflect the continuing impact which

childhood experiences have on our identity and self-confidence as adults, even

when we have developed Pride. The voices also represent the many conversations

which other people have had about me as a result of my illness - doctors,

lawyers and so on - and the impact this had on me at a time when I found

it very hard to conduct a conversation myself.

The piece itself is written in 4/4 at 120 beats per minute, which

allows the notes themselves to be heard at intervals of a second, underlining

the theme of time passing. This tempo is the standard for modern dance music,

and I hope gives pace to what is apparently a slow-moving piece, as well as

reflecting the fact that Layla and I enjoy going clubbing together.

In general the sounds are derived from the sounds which I recorded

during the 24-hour ECG - for example the use of voices is derived from

the voices I recorded at the hospital - but I've either re-recorded

sounds for a specific, more focused use or have used synthesised versions of

them. I've enjoyed using obviously synthetic versions of what should be

ambient noises - for example of wind, thunder and waves - reflecting

the fact that it's a very stylised piece.

The second part of 'Fight' illustrates the way that,

in my early to mid-30s, I developed self-knowledge and Pride in a disabled identity.

This started when I became suddenly much more disabled through the sudden onset

of spinal degeneration, which left me with no identity at all. I have always

described the onset of my condition as like being struck by lightning, and I

taped the sounds of thunder and rain during the 24-hour ECG, so I decided to

use the sound of thunder to illustrate this life change.

The sound of the heartbeat, meanwhile, is taken from the ECG

experience itself, although it has nothing to do with the original wave pattern.

The tempo is also consistent with a real heart beat.

Developing Pride was a journey of self-discovery; a process not

a moment, and so I continued to use the sound of traffic to illustrate this

alongside the images of reflections in the second half of the piece. The use

of reflections also illustrates the continuing impact of childhood experiences

on our adult self-image, although the voices are now absent.

During this period of my life I was able to re-judge and forgive

my younger self for being 'wrong', 'poor' and 'bad',

and integrate the parts of me - as a sexual person, as a dancer, musician

and artist - that previously I had cast out for being a failure. The second

part of 'Fight' illustrates this, as Layla and I acknowledge each

other and find ways of achieving a balance between us.

There are several other themes within 'Fight', including several

I am sure that I am not consciously aware of myself! But what I want to do now

is to open this up to questions . . .

Illustration: Detail of Ju from Melanie

Manchot's triptych of Ju Gosling and Andrew Logan

© The City Gallery,

Leicester and the artists: 2001

This site was built by Ju

Gosling aka ju90 during an artist's residency at Oriel

31 in November 2001

Return to top of page

I'm

going to divide this talk into three parts. First, I'm going to talk about my

own experiences of disability aids and equipment over the past few weeks, in

order to give you some insight into the relationships which disabled people

have with their aids and equipment and with the people who provide them. Then

I'm going to talk to you about my video installation which is being shown in

this exhibition, 'Fight', and about how it was developed and what its meaning

is to me. Then I'm going to open it up to discussion, where you can ask questions

and make your own points about the exhibition and its themes.

I'm

going to divide this talk into three parts. First, I'm going to talk about my

own experiences of disability aids and equipment over the past few weeks, in

order to give you some insight into the relationships which disabled people

have with their aids and equipment and with the people who provide them. Then

I'm going to talk to you about my video installation which is being shown in

this exhibition, 'Fight', and about how it was developed and what its meaning

is to me. Then I'm going to open it up to discussion, where you can ask questions

and make your own points about the exhibition and its themes.